I should point something out before I begin: This post will include some personal observation and analysis in addition to the hard numbers. When writing about statistics (particularly those that have a, shall we say, feminist nature), people will eventually try to prove that your numbers are actually wrong. It's hard to reject the publisher stats (though some have tried), but somehow people eventually reach a particularly toxic - and at times racist - argument.

But let's not get ahead of ourselves.

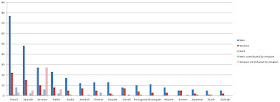

We left off with an industry-wide problem and an overall rate of translation at 31%. At this point, I decided to look more specifically at the language breakdown of the books published. Part of this is out of pure curiosity, but most of this has to do with the question of whether women are poorly translated worldwide, or if this is a geographically isolated problem.

Methodology

Once again, my numbers come from the US-based Three Percent database and are for first-time translations of fiction and poetry only. A single title by an author of unknown gender (translated from German) was removed for the sake of simplicity. The cutoff value for the country/language specific charts was at least 7 titles published, in order to better see the data. As always, there is a chance of some inconsistencies/inaccuracies due to human error...

Breakdown by countries and languages

|

| Click to enlarge |

|

| Languages, excluding AmazonCrossing |

But what about countries, I can hear you ask? Surely languages aren't especially representative, since of course Spanish spans three or so continents, French at least three, Russian an entire swathe of Asia and Europe... surely there's some major difference with countries, right?

Not quite. France remains the overwhelmingly dominant voice, and since French translations remain dismally disproportionate in not-translating women writers, it's not especially surprising that the overall ratio looks not unlike France's.

And still, the rest of the world doesn't do all that well either. I decided to try to find the countries with the best track record, the area of the world so often touted as egalitarian and supportive of women and progressive and... you get the point. So yes, I looked only at the Nordic countries:

Hmm. Not that great either.

The narrative of "some parts of the world"

I think I need to pause here for a moment and explain what it is exactly that I'm trying to show. You see, there's this one argument I'm constantly told whenever I talk about this imbalance: The problem of women in translation is surely as a result of "some parts of the world being more oppressive to women". Western readers frequently imply that the entire project is meaningless, since of course there are going to be cultures in which women simply aren't valued as highly as men. This is almost always code for "the rest of the world is sexist, but the West has advanced beyond that".

This is a claim that has not only always angered me greatly because of how heavily racially coded it is, but more to the point angers me because of how distinctly false it is. Look at the charts above. Do you usually include France in your list of "oppressive to women"? What about Sweden? Boy, Spain sure does have a poor track record. And goodness me, Norway, that bastion of oppression!

By languages too. I have most frequently heard readers and industry-folk alike try to argue that Arabic would have significantly lower rates of translation than other languages. And while it's true that women writers make up only 23% of translations from Arabic, that's the same ratio you find for, well, French. It's the same ratio you find for Japanese (22%), only a little less than the ratio you find for Portuguese (27%) or Spanish (29%). Any claims that attempt to dismiss the problem of women in translation by limiting them to "certain parts of the world" are not only false, they are racist. They presume a cultural superiority by one specific slice of the world which - guess what - is doing just as poorly as almost everywhere else. At times, even worse, especially given how many more books they get translated per year.

This is what it looks like by continent of origin. Europe, the Americas and Asia all hover around the 31% (plus or minus), and Africa generally does lag behind. But of course, the entire African continent accounts for a grand total of 31 titles, making its lower rate of translations less prominent. Europe remains the primary source of all translations, and we're still left with a fairly global problem.

I also looked within Europe. This metric is probably the sketchiest and least accurate, because my definition of Western versus non-Western Europe was extremely vague. Basically anything east of Germany and the entire Baltic region got called "non-Western", but this is mostly just a guided attempt to show the differences between the two regions:

And here there is a marked difference - Western Europe at an unsurprising 35%, while the smaller countries (with far fewer translations) don't even reach 20%. That's something worth remembering for the future.

Final takeaways

I want to reiterate that these numbers are all extremely skewed, and to a certain degree almost meaningless. When one language and one country and one part of the world is so dominant in all of translation (a topic that should be discussed separate of the women in translation project...!), it makes it hard to recognize the weight behind any of the other numbers. French's 23% translation rate is obviously much more significant than, say, Tamil's 100% (which results from one book). But even with that, it's impossible not to recognize that there is no part of this world - no language or country or continent - that is doing well. The problem of women writers in translation is global, and while some countries technically have parity or even ratios above 50%, their weight is generally not so prominent (with the exception of German, where the numbers shift drastically without one publisher).

We cannot blame "some" regions of the world for a failure to give voice to women writers, and we cannot attempt to make this some sort of cultural distinction when it is effectively universal. We can only continue to discuss the gross imbalance and seek ways in which to rectify it across the board.