Introduction

Here's the thing about math: Cold as it may be, it can often hide pervasive truths. Numbers don't lie, but they can mislead. They can omit. And sometimes, even as they tell the truth, they hide its depth and scope.

I've been publishing yearly statistics for a while now, but each time it feels like a snapshot. Every year, I get comments along the lines of "okay, but this is just an outlier" or "the average is skewed" or something to that extent. If we're being fair, these arguments aren't wrong. If a publisher is consistently doing good work in terms of publishing women in translation and suddenly has a bad year, isn't it a little silly to single them out? Wouldn't we expect to see some fluctuation in the rates of publication and publication trends themselves?

And so I did what any reasonable scientist would do: I decided to look at the bigger picture. Instead of analyzing data year-by-year, I decided to look at the past five years as a whole (2013-2017), representing the five WITMonths that mark this project.

The problem is that the data doesn't actually change. Yes, numbers may hide nuances, but in this case... they don't. That generally unchanged average of 28-30% publication of women in translation? It's unchanged because most of the prominent publishers of literature in translation haven't changed anything. Not in their averages, and not year by year. As you will see, there's a disheartening lack of progress. Hopefully seeing these numbers laid out will trigger the realization that yes, something needs to change.

Results

The first thing I decided to look at was the total number of books published from 2013-2017. I selected major publishers based on their overall translation publication rates, and mapped out the flat sum of books published by men or by women. As you can see, overall publication rates vary widely between different publishers, with some "major" publishers only releasing 15 or so books over five years. Even so, it's very easy to see that the overwhelming majority of publishers not only publish more men than women in translation, but do so at staggering rates. This becomes even more apparent in the figure below:

If 30% has been the approximate base rate of publishing women writers in translation for every year since 2013, it seems likely that most major publishers would simply hover around this rate. It turns out that this isn't actually true, and that the influence of a single publisher - AmazonCrossing - is even greater than I had previously assumed (alongside the significantly more minor effect of smaller publishers, which I did not include in these counts). If we take the grand sums of all of the top publishers, the rates of publication of women writers look fairly similar to those yearly values: 31% books by women writers. But if we remove AmazonCrossing, the rate fairly plummets to 24%.

It's not hard to see why. Out of the major publishers, only two even reach 50% (Deep Vellum at a solid 1:1, AmazonCrossing at 61%), with 5 additional publishers crossing the industry average of 30% (Other Press, Open Letter, HMH, Bitter Lemon, and Atria). There are then a few publishers that hover around the industry average (Europa Editions, Seagull Books, Graywolf, Minotaur) and publish just over 25% women in translation, followed by a shocking sequence of 15 big-name, high-prestige, acclaimed publishers of literature in translation that don't even come close. Publishers like Dalkey Archive, New Directions, Archipelago, Gallic Books, Knopf... it's not even an imbalance, as much as an outright lack.

This made me wonder whether I was missing something fundamental. In order to make sure these numbers weren't as a result of a single outlier, I looked at each of the five years individually for six major publishers, going both by sheer numbers of books translated and publishers who were frequently associated with publishing literature in translation.

There are a few interesting takeaways from this breakdown. First: It's interesting to note that AmazonCrossing wasn't always as focused on publishing women in translation as it is today. It also shows that the 60% rate cited above is a low-ball, shifted somewhat because of 2013. Since 2014, they have published comfortably more women writers than men in translation. They remain the only major publisher to do so. (Remember that many smaller publishers such as Feminist Press consistently focus on books by women writers, even if I do not include them specifically in these stats posts!)

Things get a little complicated after that. I actually first want to highlight Open Letter, since they're a bit of an interesting case in this group. With an overall rate of 34%, they fall somewhat on the side of better publication of women writers. But as you can see, this mostly follows a back-and-forth fluctuation - one above, one below. They also never quite make it to 50%. In my mind, Open Letter serves as a great reminder of what happens if you just follow the market flow without any critical assessment. This is the ultimate baseline... and no, it isn't good enough.

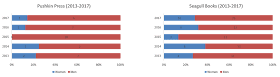

Next we have publishers like Europa Editions and Seagull Books. Both have rates just under the industry average (~28%), where it seems like a single year pushes that number just a bit lower (for Seagull, 2015; Europa, 2017). Even so, neither publisher quite manages to break free of the industry average. Europa does have one year of publishing parity, but it too is an outlier in a different way - it's the year in which they published the least amount of books in translation overall. Seagull's situation is a little more erratic, again showing how prevalent the baseline 30% really is.

In the next category, we have an interesting, singular example of a publisher that has been improving in their stats from year to year: New Directions. Despite publishing approximately the same number of books every year since 2013, they have steadily increase the share of books by women that are released per year. While they have yet to crack the base threshold (and have an abysmal 19% rate overall from 2013-2015), there is a clear upward trend. New Directions thus emerges as a unique beacon of hope when it comes to publishing women writers in translation, suggesting that this movement may actually lead to concrete change in the near future (I will discuss this more in depth in tomorrow's post).

Finally, we have a series of publishers that not only have low average rates, not only seem to publish very few women writers in translation, not only don't really change from year to year, but also simply go entire years without publishing a single book by women in translation. Take Archipelago, which does not actually publish all that many books in translation every year (but are uniquely associated with translated literature) as an example. This is a publisher that comfortably did not publish a single book by a woman writer in translation in both 2013 and 2015. Dalkey Archive is its counter, a publisher that puts out a massive amount of literature in translation every year, yet also managed to go the entirety of 2014 without publishing a single book by a woman writer in translation (I've written about this before, of course, quite specifically). Gallic Books, Pushkin Press, and NYRB all also have at least one year in which no women in translation were published. Interestingly, for both NYRB and Gallic Books, years in which women weren't published amount to the years in which they published fewer books overall. This should not be an excuse, however; books by women in translation are not simply add-ons, with room leftover only after the men have had their chance. In the other direction, Pushkin Press published its highest number of books in 2015, the same year it published zero books by women in translation.

There is, however, important context missing behind this data. First: The wonderful Three Percent Database on which I based these numbers has its own biases, for instance the limited focus on fiction and poetry, the lack of YA/children's literature, the omission of previously released/translated titles... Several of these publishers (Pushkin, Archipelago, NYRB) publish many additional books in translation that simply aren't getting counted here. However. I looked over the catalogs of each of these publishers, specifically those books that do not make it into the Three Percent Database. The situation not only does not much improve, it often gets worse. Archipelago, for instance, has an entire publishing line specifically for children's literature, in which I found a rate of below 20% (children's literature! that field allegedly so dominated by women!). For many academic-associated publishers, the situation is far worse, as there is a huge imbalance in nonfiction translations.

|

| W - women, M - men, B - both |

These numbers are, quite frankly, enraging. They demonstrate an across-the-board lack of interest in the women in translation project, alongside the global stagnation I've described in previous posts. Publishers of literature in translation are supposed to be showing us the best that the world has to offer, but how can that possibly be true if we are only seeing a tiny fraction? (And don't forget that an overwhelming slice of these titles is from Western/Northern Europe!) Something has to change.

...and so I decided to do something about it.

To be continued.

Now this is a cliffhanger of a post! Your numbers are irrefutable. It is time for change.

ReplyDeleteWow. Laid out like this, the numbers are impressive and damning.

ReplyDeleteVery discouraging. I've seen it from the perspective of trying to choose a non-European woman writer being published by an independent publisher during a certain month (to have for the Asymptote Book Club) - nearly impossible to find!

ReplyDelete