I've been thinking about the Nobel award winners for 2018 and 2019 quite a bit for the past few days. It's hard not to; pretty much every winner in the past few years has had some degree of controversy, not to mention the shameful scandal that led to the Nobel to push off the 2018 award to this year in the first place. But something about this year feels extra frustrating and disappointing, possibly because there are two winners and that only emphasizes all of the flaws inherent in the award.

Also, one of the winners is... not great. We'll get to that in a moment.

Like many readers, I used to have great admiration for the Nobel prize. When I was a teenager and starting out work on this blog, I wrote a full list of all of the Nobel winners in a notebook and marked which I wanted to read, at what priority, which work I most wanted to read... and I set myself the goal of reading through all of them. That project fizzled quickly, once I realized how mediocre a lot of writers were (particularly in the early 20th century) and once I started to feel how imbalanced the list was. Once I started working on expanding my definition of the canon, it felt even more outdated to focus on Nobel winners in particular - why bother with a list of European men?

My shift in opinion doesn't match reality, in as much as regular readers are still mostly influenced by the "big name" awards than they'll ever be by... smaller and more obscure literary movements. (*cough*) The Nobel award winners are published in almost every major news outlet in the world. Their books are typically translated widely and sell (reasonably) well. A Nobel carries weight in a way that no other international award does.

So let's talk about why this year's award is so disappointing.

In 2018, an alternate Nobel ("New Academy Prize in Literature") was given to the French-Guadeloupean author Maryse Condé. The prize was seen as a bit of a filler, a "kiddie" award that was quickly dissolved. Condé was a noble choice - she is a remarkably good and diverse writer whose works absolutely deserve greater exposure and attention. Sidelined as the alternate Nobel may have been, it nonetheless gave some degree of attention to an author who, frankly, is more than worthy for the "real" award.

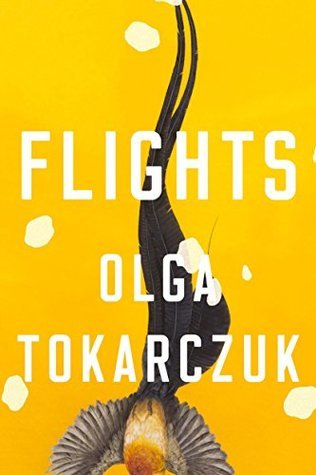

In the leadup to the double-awarding of 2019, the Nobel committee seemed eager to smooth things over with anxious readers. Just last week, the Guardian had a whole article devoted to the committee's desire to expand beyond male dominated and Eurocentric winners. It's hard not to stare at the sketches of the writers - both white Europeans - and feel cheated. Weren't we promised something different? But the disappointment feels even more tainted - I desperately want to support Olga Tokarczuk (a writer I think is also quite worthy of recognition, and one whose work Flights, for example, explicitly tackles questions of narrowmindedness and diversity) and recognize that it's still absurdly difficult for any woman writer in translation (even European!) to win a major award. Whatever else I may think of the fact that non-white European women still aren't getting any attention (and recall that there has yet to be a single women of color in translation who has won the Nobel in its entire history), I cannot be disappointed by Tokarczuk's individual win.

But, of course, it's not just that the Academy selected two white Europeans for its prize, there's also the matter of Peter Handke, the 2019 winner.

I've spent days mulling this over and wondering how to address the matter, or indeed whether or not I should. Ultimately, I've never read and Handke and have little desire to do so; I recall seeing a description of one of his books back when I began to read a lot more literature in translation (overwhelmingly by white, European, men authors...) and thinking to myself "meh, sounds stuffy and douchey". I was largely unaware of Handke's controversial - aka awful - support of ethnic cleansing and nationalism prior to his win. But as the news got out, I saw a trickle of criticism from book bloggers, translators, and publishers on my Twitter feed that eventually became a full-on onslaught of horror, finally culminating in a PEN America denunciation. (For the record: When I began writing this post, his Wikipedia page included a paragraph on his controversies and that paragraph no longer appears. I had planned to cite this as proof of Handke's status as a controversial writer; the omission frankly feels even more telling in its clumsy attempt to whitewash Handke's messy status.)

Handke's win feels dirty from a lot of different angles. First, there's the matter of his politics. In a time of rising nationalism (and violence inherently linked to nationalism), what does it mean to give a nationalist-sympathizing, genocide-denying guy a massive prize and an effective endorsement? Separating art from artist is a heavy question I still struggle to answer (further complicated by the fact that I'm Jewish and fun fact, a lot of people in the world and throughout history have desperately wanted me dead), but there's a huge difference between separating art from artist in the sense of "okay let's publish a controversial artist for his art while acknowledging and interrogating his problems" and the question of "should we give the dude lots and lots of money, attention, fame, and a platform from which to promote hateful ideas"?

Second, there's the identity politics matter. For people who try to argue that the Nobel goes to the most worthy writers, the history of the Nobel is enough to dispute that claim. It is obvious that talented writers from around the world are constantly looked over, whether because of genre, country of origin, language of origin, race, or even popularity (in both directions...). Women in particular have long been looked over, and I can easily name several women writers from around the world who passed away in the past decade alone who deserved the prize far more than a solid third of the actual winners. When the Nobel committee makes the explicit claim to notice and care about the historic imbalance in their award and then continues to give it to white European men, they are trying to have it both ways. Yes, addressing the imbalance in the award is important! they admit. But we're not going to do anything about it if it means that we have to stop awarding the prize to white European men.

I'm left feeling bitter and disappointed. Tokarczuk deserved better than this and deserves praise without an asterisk next to her name, pointing to Handke's controversies (and why, why do women always have to bear the burden of unsavory men?). I also feel like we once again got cheated out of brilliant women writers from around the world who definitely deserve more attention. Marie NDiaye. Yoko Ogawa. Banana Yoshimoto. Han Kang. Maryse Condé. Scholastique Mukasonga. Can Xue. Ambai. Isabel Allende. Nawal El Saadawi. Goli Taraghi. Ece Temelkuran. Minae Mizumura. Yanick Lahens. Ananda Devi. Dương Thu Hương. I haven't read every work these writers have written (not least because... many have not been translated into languages I speak/read in), nor can I vouch that they have not said or done objectionable things in the past as well. But I look at them and know that they have all written excellent, powerful, and life-changing books. I know that each one has contributed to the literary landscape in some form or other. They represent a wide range of cultures, experiences, and stories. And they could all benefit from the attention, money, and respect that the Nobel committee could easily bestow upon them.

The Nobel prize will always anger someone. Sometimes it might be because a winner is too obscure and your favorite didn't win. Sometimes it will be because the writer is too popular and deemed not "literary" enough by some. There's always going to be something! But at the very least, the Nobel committee can stop angering people by picking poorly... and recently, it has been. Unfortunately, it continues to be the most relevant prize in literary consciousness, which means that we readers have to work extra hard to get the word out that it is not actually reflecting on the "best" authors the world has to offer. And we need to push for it to begin to reflect the realities of the world around us. Literature is not (nor has it ever been...) white European men with a handful of English-language writers and the occasional (rare) woman writer. It is time the Nobel prize understood that.

Sunday, October 13, 2019

Saturday, August 31, 2019

WITMonth Day 31 | Another year past

This post may be a bit more... personal than most.

August 31st always seems to sneak up on me. Wasn't there so much more I wanted to do? Weren't there more posts and issues I promised to write about?

This year, there absolutely were. There were a lot of subjects I left dangling and promised to return to. And I will! But I also took a few days off from blogging these past few days after the intense compilation of the 100 Best Books by Women in Translation (100 Best WIT), what has quickly become the most popular post on the blog of all time (...by far...) and has comfortably passed the 5000 direct hits milestone. The project was extraordinarily rewarding and I am proud of the work I did to help compile the final list, but it was also very draining. I also won't pretend that it hasn't cast my own role in WITMonth in a new light - am I really that necessary as an individual?

I've promised a lot more blog posts and I will complete them. The analysis of the Hebrew-language publishing market is forthcoming, as are many more posts on the 100 Best WIT. There's so much I want to discuss, from the process of compiling the list, the ways in which its biases emerged early in the compilation, the contemporary tilt, and the degree to which I struggle with the inevitable imperfections of a crowd-sourced list. I also want to share the full list of nominations, but that will require a lot of work - I was not so organized while compiling the data and it's possible that there are errors or duplicates along the way, some which may even impact the top 100 themselves. Human error feels like an inevitable outcome here, and I will need to spend a lot of time/effort ensuring that the full list is accurate. (Not to mention, I didn't record a lot of metadata like country of origin, language of origin, or even proper spelling for most of the authors...)

There's a lot I plan to do on the blog, but I'm also going to begin to ease my foot off the gas. I adore this project and I am extremely proud of everything I've done since late 2013 and I have every intention of continuing to work on the @read_WIT Twitter and @readwit Instagram and posting and organizing and so on. But I'm not sure I'll be doing as much. I think the era of daily WITMonth posts is over, as is the urgent need to reblog/respond to all Twitter posts in the tag. The joy of having a project grow so much is that... I can't actually keep up with everything! And so I'm not going to. At the end of the day, I do this project on a purely voluntary basis, I do it with nothing in exchange (except the rare review copy, and I do mean rare), and I'm doing it alongside full time work/school. (Yay PhD life!) I want to be able to continue to enjoy this project without completely burning out. So things are going to have to change.

I love seeing how WITMonth has grown. I love seeing how WITMonth is constantly changing. I love every single blogger, Instagrammer, Booktuber, critic, publisher, translator, or whatever who takes part in WITMonth, who creates new avenues for promoting women writers in translation, who takes steps to move our cause forward. I am grateful to all of you and all of the work you all do. Another year has passed us by, and as always, from the bottom of my heart: Thank you.

August 31st always seems to sneak up on me. Wasn't there so much more I wanted to do? Weren't there more posts and issues I promised to write about?

This year, there absolutely were. There were a lot of subjects I left dangling and promised to return to. And I will! But I also took a few days off from blogging these past few days after the intense compilation of the 100 Best Books by Women in Translation (100 Best WIT), what has quickly become the most popular post on the blog of all time (...by far...) and has comfortably passed the 5000 direct hits milestone. The project was extraordinarily rewarding and I am proud of the work I did to help compile the final list, but it was also very draining. I also won't pretend that it hasn't cast my own role in WITMonth in a new light - am I really that necessary as an individual?

I've promised a lot more blog posts and I will complete them. The analysis of the Hebrew-language publishing market is forthcoming, as are many more posts on the 100 Best WIT. There's so much I want to discuss, from the process of compiling the list, the ways in which its biases emerged early in the compilation, the contemporary tilt, and the degree to which I struggle with the inevitable imperfections of a crowd-sourced list. I also want to share the full list of nominations, but that will require a lot of work - I was not so organized while compiling the data and it's possible that there are errors or duplicates along the way, some which may even impact the top 100 themselves. Human error feels like an inevitable outcome here, and I will need to spend a lot of time/effort ensuring that the full list is accurate. (Not to mention, I didn't record a lot of metadata like country of origin, language of origin, or even proper spelling for most of the authors...)

There's a lot I plan to do on the blog, but I'm also going to begin to ease my foot off the gas. I adore this project and I am extremely proud of everything I've done since late 2013 and I have every intention of continuing to work on the @read_WIT Twitter and @readwit Instagram and posting and organizing and so on. But I'm not sure I'll be doing as much. I think the era of daily WITMonth posts is over, as is the urgent need to reblog/respond to all Twitter posts in the tag. The joy of having a project grow so much is that... I can't actually keep up with everything! And so I'm not going to. At the end of the day, I do this project on a purely voluntary basis, I do it with nothing in exchange (except the rare review copy, and I do mean rare), and I'm doing it alongside full time work/school. (Yay PhD life!) I want to be able to continue to enjoy this project without completely burning out. So things are going to have to change.

I love seeing how WITMonth has grown. I love seeing how WITMonth is constantly changing. I love every single blogger, Instagrammer, Booktuber, critic, publisher, translator, or whatever who takes part in WITMonth, who creates new avenues for promoting women writers in translation, who takes steps to move our cause forward. I am grateful to all of you and all of the work you all do. Another year has passed us by, and as always, from the bottom of my heart: Thank you.

Monday, August 26, 2019

WITMonth Day 26 | The 100 Best Books by Women Writers in Translation

For the past almost-two months, readers from around the world have been sending in their nominations and votes for this list: The 100 Best Books by Women in Translation. Inspired in part by Catherine Taylor's excellent review of Boyd Tonkin's 100 Best Novels in Translation, fellow bloggers (including Twitter user Antonomasia), and subsequent conversations on this blog, the idea was to create a new canon of sorts. Every reader could send up to 10 nominations of books written by women, trans, or nonbinary authors, originally written in any language other than English. Ultimately, almost 800 unique books were nominated. Most of the titles only ever had a single vote, but it speaks to the passion and love that readers have for women writers from around the world that we reached such a number. Many people sought to promote books that they felt didn't get enough attention, or books that they hoped might someday be translated, regardless whether they expected that book to make it to the top 100. The whole list - and specifically the one comprised of untranslated-into-English books - is also a worthy one, but I'll talk about it at a later time.

Let's focus on the top 100.

First and foremost, a disclaimer: This is obviously not really a list of the 100 best books by women in translation... because no such list could ever possibly exist! Every canon will be flawed in some form or other, as I'll be discussing more over the next few days and weeks. Our list is crowdsourced and borne of reader-love; it is a list that is strongly rooted in current reading trends (even if you might be surprised by some inclusions/omissions... I certainly was!). There's a lot of ink to be spilled over just about every title that ended up making it into the top 100 and much more over those that didn't make it, but here's the bottom line: Whether or not these are truly the 100 best books by women writers from around the world, whether or not this is a flawlessly representative list, and whether or not we'd get the same list if we tried again next week (I am confident we would not), this is a list of 100 books by women writers from around the world that people loved. That's worthy in and of itself.

But enough of my thoughts! I'll have plenty of time to talk about things I find interesting, surprising, or disappointing about this list at a later time (and I assure you, I will). Instead, I now present to you...

Let's focus on the top 100.

First and foremost, a disclaimer: This is obviously not really a list of the 100 best books by women in translation... because no such list could ever possibly exist! Every canon will be flawed in some form or other, as I'll be discussing more over the next few days and weeks. Our list is crowdsourced and borne of reader-love; it is a list that is strongly rooted in current reading trends (even if you might be surprised by some inclusions/omissions... I certainly was!). There's a lot of ink to be spilled over just about every title that ended up making it into the top 100 and much more over those that didn't make it, but here's the bottom line: Whether or not these are truly the 100 best books by women writers from around the world, whether or not this is a flawlessly representative list, and whether or not we'd get the same list if we tried again next week (I am confident we would not), this is a list of 100 books by women writers from around the world that people loved. That's worthy in and of itself.

But enough of my thoughts! I'll have plenty of time to talk about things I find interesting, surprising, or disappointing about this list at a later time (and I assure you, I will). Instead, I now present to you...

The 100 Best Books by Women Writers in Translation

| Title | Author | Translator(s) into English | Language | Country | Vote tally | Original publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My Brilliant Friend | Elena Ferrante | Ann Goldstein | Italian | Italy | 26 | 2011 |

| The Vegetarian | Han Kang | Deborah Smith | Korean | South Korea | 24 | 2007 |

| Fever Dream | Samanta Schweblin | Megan McDowell | Spanish | Argentina | 22 | 2014 |

| Human Acts | Han Kang | Deborah Smith | Korean | South Korea | 19 | 2014 |

| The Door | Magda Szabó | Len Rix | Hungarian | Hungary | 19 | 1987 |

| Flights | Olga Tokarczuk | Jennifer Croft | Polish | Poland | 19 | 2007 |

| Convenience Store Woman | Sayaka Murata | Ginny Tapley Takemori | Japanese | Japan | 19 | 2016 |

| The Summer Book | Tove Jansson | Thomas Teal | Swedish | Finland | 17 | 1972 |

| The Housekeeper and the Professor | Yoko Ogawa | Stephen Snyder | Japanese | Japan | 13 | 2003 |

| The Years | Annie Ernaux | Alison L. Strayer | French | France | 12 | 2008 |

| Things We Lost in the Fire | Mariana Enríquez | Megan McDowell | Spanish | Argentina | 12 | 2016 |

| Death in Spring | Mercè Rodoreda | Martha Tennant | Catalan | Spain | 12 | 1986 |

| Drive Your Plow over the Bones of the Dead | Olga Tokarczuk | Antonia Lloyd-Jones | Polish | Poland | 12 | 2009 |

| Sphinx | Anne Garréta | Emma Ramadan | French | France | 11 | 1986 |

| Die, My Love | Ariana Harwicz | Sarah Moss, Carolina Orloff | Spanish | Argentina | 11 | 2012 |

| Kitchen | Banana Yoshimoto | Megan Backus | Japanese | Japan | 11 | 1987 |

| Persepolis | Marjane Satrapi | Mattias Ripa, Blake Ferris, Anjali Singh | French | Iran / France | 11 | 2000 |

| Disoriental | Négar Djavadi | Tina Kover | French | Iran / France | 11 | 2016 |

| The Mussel Feast | Birgit Vanderbeke | Jamie Bulloch | German | Germany | 10 | 1990 |

| The Notebook Trilogy | Ágota Kristóf | Alan Sheridan | French | Hungary | 9 | 1991 |

| Innocence | Heda Margolius Kovály | Alex Zucker | Czech | Czech Republic | 9 | 1985 |

| The House of the Spirits | Isabel Allende | Magda Bogin | Spanish | Chile | 9 | 1982 |

| The End of Days | Jenny Erpenbeck | Susan Bernofsky | German | Germany | 9 | 2013 |

| A True Novel | Minae Mizumura | Juliet Winters Carpenter | Japanese | Japan | 9 | 2002 |

| The Unwomanly Face of War | Svetlana Alexievich | Richard Pevear, Larissa Volokhonsky | Russian | Belarus | 9 | 1985 |

| Eve Out of Her Ruins | Ananda Devi | Jeffrey Zuckerman | French | Mauritius | 8 | 2006 |

| Trieste | Daša Drndić | Ellen Elias-Bursać | Croatian | Croatia | 8 | 2007 |

| Bonjour Tristesse | Françoise Sagan | Irene Ash | French | France | 8 | 1954 |

| Love | Hanne Ørstavik | Martin Aitken | Norwegian | Norway | 8 | 1997 |

| Suite Française | Irène Némirovsky | Sandra Smith | French | France | 8 | 1942 |

| So Long a Letter | Mariama Bâ | Modupe Bode-Thomas | French | Senegal | 8 | 1979 |

| The Tale of Genji | Murasaki Shikibu | Various | Japanese | Japan | 8 | 1008 |

| The Elegance of the Hedgehog | Muriel Barbery | Alison Anderson | French | France | 8 | 2006 |

| Tentacle | Rita Indiana | Achy Obejas | Spanish | Dominican Republic | 8 | 2015 |

| Kristin Lavransdatter | Sigrid Undset | Various | Norwegian | Norway | 8 | 1922 |

| Second Hand Time | Svetlana Alexievich | Bela Shayevich | Russian | Belarus | 8 | 2013 |

| Territory of Light | Yūko Tsushima | Geraldine Harcourt | Japanese | Japan | 8 | 1979 |

| The Hour of the Star | Clarice Lispector | Benjamin Moser | Portuguese | Brazil | 7 | 1977 |

| Woman at Point Zero | Nawal El Saadawi | Sherif Hetata | Arabic | Egypt | 7 | 1975 |

| Soviet Milk | Nora Ikstena | Margita Gailitis | Latvian | Latvia | 7 | 2015 |

| Notes of a Crocodile | Qiu Miaojin | Bonnie Huie | Chinese | Taiwan | 7 | 1994 |

| La Bastarda | Trifonia Melibea Obono | Lawrence Schimel | Spanish | Equatorial Guinea | 7 | 2016 |

| Vernon Subutex I | Virginie Despentes | Frank Wynne | French | France | 7 | 2015 |

| Revenge | Yoko Ogawa | Stephen Snyder | Japanese | Japan | 7 | 1998 |

| Memoirs of a Polar Bear | Yoko Tawada | Susan Bernofsky | German | Germany | 7 | 2014 |

| Nada | Carmen Laforet | Edith Grossman | Spanish | Spain | 6 | 1945 |

| Near to the Wild Heart | Clarice Lispector | Alison Entrekin | Portuguese | Brazil | 6 | 1943 |

| Strange Weather in Tokyo / The Briefcase | Hiromi Kawakami | Allison Markin Powell | Japanese | Japan | 6 | 2001 |

| Go, Went, Gone | Jenny Erpenbeck | Susan Bernofsky | German | Germany | 6 | 2015 |

| Seeing Red | Lina Meruane | Megan McDowell | Spanish | Chile | 6 | 2012 |

| Fish Soup | Margarita García Robayo | Charlotte Coombe | Spanish | Colombia | 6 | 2018 |

| The Lover | Marguerite Duras | Barbara Bray | French | France | 6 | 1984 |

| Memoirs of Hadrian | Marguerite Yourcenar | Grace Frick | French | France | 6 | 1951 |

| The Wall | Marlen Haushofer | Shaun Whiteside | German | Austria | 6 | 1963 |

| Family Lexicon | Natalia Ginzburg | Various | Italian | Italy | 6 | 1963 |

| People in the Room | Norah Lange | Charlotte Whittle | Spanish | Argentina | 6 | 1950 |

| Mouthful of Birds | Samanta Schweblin | Megan McDowell | Spanish | Argentina | 6 | 2008 |

| Poems | Sappho | Various | Ancient Greek | Greece | 6 | -570 |

| The Faculty of Dreams | Sara Stridsberg | Deborah Bragan-Turner | Swedish | Sweden | 6 | 2006 |

| Thus Were Their Faces | Silvina Ocampo | Daniel Balderston | Spanish | Argentina | 6 | 1993 |

| The Second Sex | Simone de Beauvoir | Various | French | France | 6 | 1949 |

| The True Deceiver | Tove Jansson | Thomas Teal | Swedish | Finland | 6 | 1982 |

| Faces in the Crowd | Valeria Luiselli | Christina McSweeney | Spanish | Mexico | 6 | 2011 |

| A View with a Grain of Sand | Wisława Szymborska | Stanislaw Baranczak, Clare Cavanagh | Polish | Poland | 6 | 1995 |

| The Queue | Basma Abdel Aziz | Elisabeth Jaquette | Arabic | Egypt | 5 | 2016 |

| Fox | Dubravka Ugrešić | Ellen Elias-Bursać | Croatian | Croatia | 5 | 2017 |

| The Days of Abandonment | Elena Ferrante | Ann Goldstein | Italian | Italy | 5 | 2002 |

| History | Elsa Morante | William Weaver | Italian | Italy | 5 | 1974 |

| Arturo's Island | Elsa Morante | Various | Italian | Italy | 5 | 1957 |

| Confessions | Kanae Minato | Stephen Snyder | Japanese | Japan | 5 | 2008 |

| The Ten Thousand Things | Maria Dermoût | Hans Koning | Dutch | Indonesia / Netherlands | 5 | 1955 |

| My Heart Hemmed In | Marie NDiaye | Jordan Stump | French | France | 5 | 2007 |

| The Unit | Ninni Holmqvist | Marlaine Delargy | Swedish | Sweden | 5 | 2006 |

| The Bridge of Beyond | Simone Schwarz-Bart | Barbara Bray | French | Guadeloupe | 5 | 1972 |

| Purge | Sofi Oksanen | Lola Rogers | Finnish | Finland | 5 | 2008 |

| The Story of My Teeth | Valeria Luiselli | Christina MacSweeney | Spanish | Mexico | 5 | 2013 |

| Swallowing Mercury | Wioletta Greg | Eliza Marciniak | Polish | Poland | 5 | 2014 |

| Tokyo Ueno Station | Yu Miri | Morgan Giles | Japanese | Japan | 5 | 2014 |

| The Little Girl on the Ice Floe | Adélaïde Bon | Various | French | France | 4 | 2018 |

| Extracting the Stone of Madness | Alejandra Pizarnik | Yvette Siegert | Spanish | Argentina | 4 | 1972 |

| The Remainder | Alia Trabucco Zerán | Sophie Hughes | Spanish | Chile | 4 | 2015 |

| The Seventh Cross | Anna Seghers | Margo Bettauer Dembo | German | Germany | 4 | 1942 |

| The Naked Woman | Armonía Somers | Kit Maude | Spanish | Uruguay | 4 | 1950 |

| Waking Lions | Ayelet Gundar-Goshen | Sondra Silverston | Hebrew | Israel | 4 | 2012 |

| The Quest for Christa T. | Christa Wolf | Christopher Middleton | German | Germany | 4 | 1968 |

| A Winter's Promise | Christelle Dabos | Hildegarde Serle | French | France | 4 | 2013 |

| Mirror Shoulder Signal | Dorthe Nors | Misha Hoekstra | Danish | Denmark | 4 | 2015 |

| Sweet Days of Discipline | Fleur Jaeggy | Tim Parks | Italian | Switzerland | 4 | 1989 |

| Zuleikha | Guzel Yakhina | Lisa Hayden | Russian | Russia | 4 | 2015 |

| The Hunger Angel | Herta Müller | Philip Boehm | German | Romania / Germany | 4 | 2009 |

| Please Look After Mom | Kyung-sook Shin | Chi Young | Korean | South Korean | 4 | 2008 |

| Like Water for Chocolate | Laura Esquivel | Thomas Christensen, Carol Christensen | Spanish | Mexico | 4 | 1989 |

| La Femme de Gilles | Madeleine Bourdouxhe | Faith Evans | French | Belgium | 4 | 1937 |

| The History of Bees | Maja Lunde | Diane Oatley | Norwegian | Norway | 4 | 2015 |

| The Weight of Things | Marianne Fritz | Adrian Nathan West | German | Austria | 4 | 1979 |

| Translation as Transhumance | Mireille Gansel | Ros Schwartz | French | France | 4 | 2014 |

| Out | Natsuo Kirino | Stephen Snyder | Japanese | Japan | 4 | 1997 |

| Our Lady of the Nile | Scholastique Mukasonga | Melanie L. Mauthner | French | Rwanda / France | 4 | 2012 |

| Subtly Worded | Teffi | Anne Marie Jackson, Robert Chandler | Russian | Russia | 4 | 1990 |

| The Letter for the King | Tonke Dragt | Laura Watkinson | Dutch | The Netherlands | 4 | 1962 |

Sunday, August 25, 2019

WITMonth Day 25 | Dying in a Mother Tongue by Roja Chamankar | Minireview

As always, I remain totally stumped when it comes to reviewing poetry. What can I say, other than "I liked this collection!"? The book - not even 70 pages including the translator's note/introduction - feels like a cool summer breeze that passed over me. It gave me immense pleasure as I encountered it and it left a soft memory on my skin. It made me feel something in a distinctly positive sense. But there's not much I can say or do once it's passed. It's passed! That's it!

As always, I remain totally stumped when it comes to reviewing poetry. What can I say, other than "I liked this collection!"? The book - not even 70 pages including the translator's note/introduction - feels like a cool summer breeze that passed over me. It gave me immense pleasure as I encountered it and it left a soft memory on my skin. It made me feel something in a distinctly positive sense. But there's not much I can say or do once it's passed. It's passed! That's it!I guess I can say: Read this, you might enjoy it. You might enjoy, like I did, the diversity in styles between the different poems. You might appreciate, like I did, the way certain poems seem to continue each other (sometimes intentionally and sometimes maybe less so). You might learn about new writers and literary traditions from the translator's note, like I did, and find yourself nodding in agreement with Blake Atwood's description of Roja Chamankar's poems as both "intimate" and "marked by disappointment and loss". You might just like the poems themselves, the translation, the language, and the way the poems feel like they're ready to jump off the page into a new dimension.

You might enjoy this collection. I certainly did.

Note: I received this book for review from the publisher.

Saturday, August 24, 2019

WITMonth Day 24 | Stats (part 3) | Introducing a new project

One of the biggest lingering questions facing the women in translation movement has to do with... the world. Literature in translation is a nice catchphrase, but when we focus so much on English, it's easy to forget that the reason the literature is in translation is because it's originally written in other languages. Most literature does not get translated, not into English and not into other languages across the globe. Anywhere you go, you're likely to find a degree of marginalization in translation, simply because only select titles even get to breach that gap... and fewer still break out into the mainstream.

People have long asked what the source of the "women in translation" problem is. When we're talking about translations into English, it's obvious that there's a huge problem (see: literally every stats post prior to this one...), but there's a legitimate question to be had regarding source languages. If women writers are thoroughly underrepresented in their original countries/languages, doesn't it stand to reason that they'd be underrepresented in English (or other) translation as well?

I'll note that I don't actually buy this claim. Translation is a form of selection/curation, and as with all cases in which specific, select titles are chosen, there is absolutely no reason to adhere to "natural" forces and not choose with a sharper eye. As I've argued before, exclusion is a choice.

But let's get back to that question: How are women writers represented in other languages and countries? What can we learn about how women are then represented in translation, and specifically in translation into English?

As you can imagine, these aren't easy questions to answer or approach. For starters, it's hard to know what goes on in other languages when you don't speak those languages! Luckily, I do happen to speak one other language fluently and I do happen to have a degree of familiarity with another country's publishing industry, and so I decided to carry out a new project this year and see whether I could begin to answer the above questions.

I began by selecting a few major Israeli publishers and examining their catalogs over two years - 2017 or 2018. Simply put, I do not have the time or resources to compile a more comprehensive list, much as I'd love to. I wanted to look at a few different matters. First of all, I have long had the feeling that the translation rate out of Hebrew (just around 33% women writers) is not reflective of the actual Israeli market. Women writers are extremely popular here, often topping the bestseller charts. Could it possibly be that the rates in English are actually representative of a bias in Hebrew itself that I've simply never noticed? I wanted to compare overall publication of original titles by men and women, to see what that source of the problem in English really is.

Then there's the question of translations. Every time I walk into a bookstore or go bookhunting during Hebrew Book Week, I always have to explain to the booksellers that I'm explicitly not seeking books originally written in English, since I would much rather read those books in the original. Time after time, I have seen the booksellers' faces drop somewhat, and they begin to scramble to find alternatives. I have long felt that translations from English dominate the Israeli book market, not just in terms of all literature in translation, but even in comparison to original Hebrew-language literature. And this in turn led to my final question: What of those translations? Are women writers well represented in translation between different languages?

There's a lot to learn from what I found.

(To be continued...)

People have long asked what the source of the "women in translation" problem is. When we're talking about translations into English, it's obvious that there's a huge problem (see: literally every stats post prior to this one...), but there's a legitimate question to be had regarding source languages. If women writers are thoroughly underrepresented in their original countries/languages, doesn't it stand to reason that they'd be underrepresented in English (or other) translation as well?

I'll note that I don't actually buy this claim. Translation is a form of selection/curation, and as with all cases in which specific, select titles are chosen, there is absolutely no reason to adhere to "natural" forces and not choose with a sharper eye. As I've argued before, exclusion is a choice.

But let's get back to that question: How are women writers represented in other languages and countries? What can we learn about how women are then represented in translation, and specifically in translation into English?

As you can imagine, these aren't easy questions to answer or approach. For starters, it's hard to know what goes on in other languages when you don't speak those languages! Luckily, I do happen to speak one other language fluently and I do happen to have a degree of familiarity with another country's publishing industry, and so I decided to carry out a new project this year and see whether I could begin to answer the above questions.

I began by selecting a few major Israeli publishers and examining their catalogs over two years - 2017 or 2018. Simply put, I do not have the time or resources to compile a more comprehensive list, much as I'd love to. I wanted to look at a few different matters. First of all, I have long had the feeling that the translation rate out of Hebrew (just around 33% women writers) is not reflective of the actual Israeli market. Women writers are extremely popular here, often topping the bestseller charts. Could it possibly be that the rates in English are actually representative of a bias in Hebrew itself that I've simply never noticed? I wanted to compare overall publication of original titles by men and women, to see what that source of the problem in English really is.

Then there's the question of translations. Every time I walk into a bookstore or go bookhunting during Hebrew Book Week, I always have to explain to the booksellers that I'm explicitly not seeking books originally written in English, since I would much rather read those books in the original. Time after time, I have seen the booksellers' faces drop somewhat, and they begin to scramble to find alternatives. I have long felt that translations from English dominate the Israeli book market, not just in terms of all literature in translation, but even in comparison to original Hebrew-language literature. And this in turn led to my final question: What of those translations? Are women writers well represented in translation between different languages?

There's a lot to learn from what I found.

(To be continued...)

Friday, August 23, 2019

WITMonth Day 23 | The Baghdad Clock by Shahad Al Rawi | Review

The Baghdad Clock's cover and marketing is both exactly what it seems like and not quite what it's sold as. With a blurb that seems to set the story predominantly during the Gulf War, the book surprises somewhat in how quickly it moves past that war and focuses on the remainder of life in the aftermath (...within scant pages, to be honest). Yet it also hints at the type of story this is - my hardcover edition comes with shiny gold print and dots circling the edges of the cover. These make The Baghdad Clock feel a little... ethereal.

It's hard for me to describe The Baghdad Clock, written by Shahad Al Rawi and translated from Arabic by Luke Leafgren. Generally speaking, I liked the novel. It's not the sort of book that necessarily excels at every technical beat, but it does a reasonable job at enough different things that the end result is a good book. The writing style is very straightforward, though sometimes a little old-fashioned in a combination that didn't always work for my taste. Pretty much everything about the book is solid, but that's also a little bit of what made me a little cooler toward it in the end; it didn't spark particularly strong emotions in me in one way or the other.

At its core, The Baghdad Clock is a coming-of-age story. This is the part that felt undersold in the marketing - it felt at times like The Baghdad Clock was being framed as more political/about war than it actually is. Which is not to say that the book isn't political (it covers some serious ground), rather that my initial reading of the blurb leaned more towards a "war story" than "girlhood" story. It ends up being a little bit of both. While there is little of the Gulf War in the book itself, its shock-waves clearly felt throughout the narrator's childhood. Moreover, the back half of the book settles into more recent Iraqi wars and turbulence. It's still not an explicit war story, but it lives in themes of war, sanctions, and uneasy peace.

Even so, the coming-of-age narrative remains dominant. Like many books of this sort, the book skips along through childhood relatively quickly, slowing down for the narrator's teenage years and early adulthood. It's important to note that while the narrator is unnamed, she is very much our guide within this story. Not only does she filter her best friend Nadia's stories through her own experiences, the narrator also tells of her neighborhood at large. As the story progresses, she humanizes her neighborhood more and more, almost as though it itself is a living character in her story.

By the novel's end, we definitely feel that we've encountered the world through the eyes of a specific girl (our unnamed narrator), but also that we've met her friends and neighbors. She remains somewhat elusive, though. The narrator shares bits of her budding romance with a neighborhood boy, but we learn little about her family life or even much about her personal aspirations. This too may have influenced how I felt about the book overall; I felt like the narrator was someone I just spent hours with, without really knowing who she was. A huge part of reading for me lies within the personal connection. Here, The Baghdad Clock almost explicitly sought to keep some distance between reader and main character. It's something I imagine won't bother most readers as it did me, but it still affected how I read the book.

But like I said: Pretty much everything about the book is... solid. The pacing is good. The way Al Rawi builds and populates her neighborhood is good. The way the story sometimes feels entirely real and sometimes just a little bit otherworldly is good. (This was actually one of my favorite touches and I would have been happy to have some more almost-fantasy in the story.) The story is interesting, the characters are solid, and the writing is fine. It's the sort of book I'd passively recommend, if it comes up. It might not make my "favorites" list any time soon, but I think readers are largely in for a good read.

Thursday, August 22, 2019

WITMonth Day 22 | A vlog about the #100BestWIT!

A vlog! They happen, on occasion.

In which I ramble about the 100 Best Books by Women in Translation and some plans for the future list!

In which I ramble about the 100 Best Books by Women in Translation and some plans for the future list!

Wednesday, August 21, 2019

WITMonth Day 21 | The Barefoot Woman by Scholastique Mukasonga | Minireview

Some of you might remember that I'm quite a fan of Scholastique Mukasonga's writing. In fact, I still cite Cockroaches as one of my absolute favorite books of the past few years. It's a powerful gut-punch of a memoir, beautiful and heartbreaking and essential all at once. While I certainly liked Our Lady of the Nile (Mukasonga's earlier-translated novel), it has not had the same sort of lasting effect that has turned Cockroaches into one of my favorite books. It was obvious to me that I'd have to read Mukasonga's newly released The Barefoot Woman, though I kept reminding myself that it would likely not hit me to the same degree.

And, indeed, it didn't, in exactly the way I expected. The Barefoot Woman is far from a bad book or mediocre memoir; on the contrary, it's quite good. Slim, concise, and achingly real, The Barefoot Woman recounts Mukasonga's memories of her mother Stefania and her childhood home. Through her mother, Mukasonga describes details of Rwandan - Tutsi - life. There's a cultural reckoning here, alongside deeply personal and traumatic memories. It's hard not to recognize The Barefoot Woman as that combination of powerful and beautiful.

And, indeed, it didn't, in exactly the way I expected. The Barefoot Woman is far from a bad book or mediocre memoir; on the contrary, it's quite good. Slim, concise, and achingly real, The Barefoot Woman recounts Mukasonga's memories of her mother Stefania and her childhood home. Through her mother, Mukasonga describes details of Rwandan - Tutsi - life. There's a cultural reckoning here, alongside deeply personal and traumatic memories. It's hard not to recognize The Barefoot Woman as that combination of powerful and beautiful.

It's important to come into the memoir knowing that The Barefoot Woman is not seeking to replicate Cockroaches. While touching on similar themes and addressing Mukasonga's own past, The Barefoot Woman feels like it's much less about the Tutsi genocide than it is about the Tutsi. Often, it is more specifically about Mukasonga's mother - focused, directed, and intimate. It's neither a sequel nor a prequel to Cockroaches; at best, this could be called a companion piece, but truthfully it felt like it deserves its own space. It's a very different sort of book, at once more mainstream in its humanity and yet unique in its internal conflicts. I can't say that this had the same effect on me as Cockroaches, but it remains a very good memoir, well worth reading.

And, indeed, it didn't, in exactly the way I expected. The Barefoot Woman is far from a bad book or mediocre memoir; on the contrary, it's quite good. Slim, concise, and achingly real, The Barefoot Woman recounts Mukasonga's memories of her mother Stefania and her childhood home. Through her mother, Mukasonga describes details of Rwandan - Tutsi - life. There's a cultural reckoning here, alongside deeply personal and traumatic memories. It's hard not to recognize The Barefoot Woman as that combination of powerful and beautiful.

And, indeed, it didn't, in exactly the way I expected. The Barefoot Woman is far from a bad book or mediocre memoir; on the contrary, it's quite good. Slim, concise, and achingly real, The Barefoot Woman recounts Mukasonga's memories of her mother Stefania and her childhood home. Through her mother, Mukasonga describes details of Rwandan - Tutsi - life. There's a cultural reckoning here, alongside deeply personal and traumatic memories. It's hard not to recognize The Barefoot Woman as that combination of powerful and beautiful.It's important to come into the memoir knowing that The Barefoot Woman is not seeking to replicate Cockroaches. While touching on similar themes and addressing Mukasonga's own past, The Barefoot Woman feels like it's much less about the Tutsi genocide than it is about the Tutsi. Often, it is more specifically about Mukasonga's mother - focused, directed, and intimate. It's neither a sequel nor a prequel to Cockroaches; at best, this could be called a companion piece, but truthfully it felt like it deserves its own space. It's a very different sort of book, at once more mainstream in its humanity and yet unique in its internal conflicts. I can't say that this had the same effect on me as Cockroaches, but it remains a very good memoir, well worth reading.

Tuesday, August 20, 2019

WITMonth Day 20 | Stats (part 2) | Where do we still need work?

I left the previous post on a cliffhanger. The truth is, I wanted a full post that detailed the positive. A lot of good things are happening in the world of literature in translation, and for women in translation in particular! WITMonth is bigger than ever and the movement is starting to have a real impact on translation rates. We should definitely take a moment (or more...) to celebrate that.

The problem is that despite all of the good, we've still got a lot of bad. It's not just an individual publisher matter, either. There's a systemic problem when you start to look at publishers who define themselves in certain ways, those who engage with WITMonth, and those who distance themselves from it.

Take Archipelago Books. This is a publisher I've been tracking for years, with the knowledge that they're one of the yearly disappointments. And so I was not particularly surprised by what I got: Archipelago sits at an 18% publishing rate of women writers in 2019. Year after year, Archipelago has proven to be one of the least WIT-friendly publishers. Considering how many of my favorite works by women in translation have been put out by them, it's disheartening that they don't seem to be making any effort whatsoever to balance out their catalog.

But, I reassured myself, they also have a children's literature imprint! Archipelago: Elsewhere Editions is an imprint devoted to international, quality literature for children. We all know, of course, of the "industry bias" towards women in children's literature, right? (...right?) Imagine my surprise, then, when it turned out that all 4 books published by this imprint in 2019 were books by men. That puts women in translation at 13% between the combined catalogs. That is... honestly inexcusable. When I reached out for comment, the response was a friendly reassurance that the publishers are aware of the imbalance and seeking to correct it, alongside a list of recent and forthcoming releases. My policy has been, until now, to give publishers the benefit of the doubt when they express an interest in improving things. I hope that next year I'll be able to add Archipelago to the list of publishers on the rise.

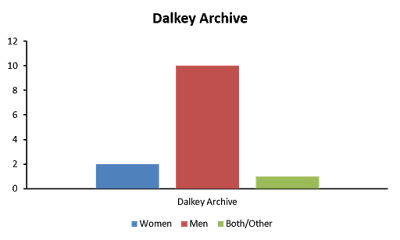

Dalkey is another eternal disappointment. Despite not having a publicly available catalog, I collected publication data from Amazon (seriously, that's all I could think of...) and was distinctly unsurprised to count 2 books by women in translation (alongside one mixed anthology), compared to 10 by men. How sad is it that 23% is still fairly good for Dalkey? Let's move on...

It's the last category that I want to talk about the most, though. We've already discussed how things are getting better among literary publishers, and my hope is that they'll continue to do so. We've seen that there's consistent improvement among titles in the Translation Database, but as Chad Post has been reiterating the past few weeks, there are still issues. I explained in my last post that I decided on a different methodology this year, opting out of using the Translation Database in favor of reviewing select publisher catalogs myself. In this way, I hope to include a wider range of genres, categorizations, and books overall, specifically kidlit, nonfiction, and previously published titles. And so the best way to look at the latter two categories is to analyze what's going on in university presses.

University presses have long been bastions of fascinating, diverse, and important literature. They are often the first to "rediscover" lost masterpieces, they publish works by researchers from around the world (and in just about every imaginable field), they push boundaries, and they have published some of my favorite books from the past few years, personally. I find university presses to be remarkably important in the grand scheme of literature in translation. It is therefore doubly disappointing that they are among the worst offenders when it comes to publishing women writers in translation. I looked at four different university presses that had enough titles in translation to be able to conduct statistics (and also easily searchable catalogs) and found that university presses remain abysmal when it comes to publishing women writers in translation: The four published a combined total of 22 women writers (plus another 7 cases of books with multiple authors) to 117 men writers in translation. That means that men make up 80% of the books in translation published by university presses, with mixed groups responsible for 5% and women 15%.

Fifteen percent.

Academic presses are important for a lot of reasons, but it's important to remember why this stings a bit more than most of the other low-rated publishers: Academic presses carry with them a degree of prestige, canonization, and clout. Having so few works by women writers and even fewer works by women writers from around the world merely perpetuates our existing (flawed) assumptions about academia, women, and women's contributions to culture and science. Women have been contributing to the canon for literally the entire span of human history... why is this still erased? It's like another publisher - Penguin Classics - which published exactly zero works by women writers in translation this past year (versus four by men in translation). There are countless classic and modern works by women writers from around the world that deserve our attention and scholarship. We're still not there.

We have a long road ahead of us with many different problems to tackle. As the rates of women in translation steadily rise for fiction and poetry and as women in translation begin to receive the recognition they deserve in the English-language world (for example, the recent Man Booker International shortlist!), we can turn our attention to other matters. Why are there still so few children's stories in translation? Why is nonfiction in translation as dominated by men writers as it is? What's going on in other languages? Some of these are question we can't answer quite yet or still don't have solutions for.

But some of these questions we can begin to answer. Stay tuned...

The problem is that despite all of the good, we've still got a lot of bad. It's not just an individual publisher matter, either. There's a systemic problem when you start to look at publishers who define themselves in certain ways, those who engage with WITMonth, and those who distance themselves from it.

Take Archipelago Books. This is a publisher I've been tracking for years, with the knowledge that they're one of the yearly disappointments. And so I was not particularly surprised by what I got: Archipelago sits at an 18% publishing rate of women writers in 2019. Year after year, Archipelago has proven to be one of the least WIT-friendly publishers. Considering how many of my favorite works by women in translation have been put out by them, it's disheartening that they don't seem to be making any effort whatsoever to balance out their catalog.

But, I reassured myself, they also have a children's literature imprint! Archipelago: Elsewhere Editions is an imprint devoted to international, quality literature for children. We all know, of course, of the "industry bias" towards women in children's literature, right? (...right?) Imagine my surprise, then, when it turned out that all 4 books published by this imprint in 2019 were books by men. That puts women in translation at 13% between the combined catalogs. That is... honestly inexcusable. When I reached out for comment, the response was a friendly reassurance that the publishers are aware of the imbalance and seeking to correct it, alongside a list of recent and forthcoming releases. My policy has been, until now, to give publishers the benefit of the doubt when they express an interest in improving things. I hope that next year I'll be able to add Archipelago to the list of publishers on the rise.

Dalkey is another eternal disappointment. Despite not having a publicly available catalog, I collected publication data from Amazon (seriously, that's all I could think of...) and was distinctly unsurprised to count 2 books by women in translation (alongside one mixed anthology), compared to 10 by men. How sad is it that 23% is still fairly good for Dalkey? Let's move on...

It's the last category that I want to talk about the most, though. We've already discussed how things are getting better among literary publishers, and my hope is that they'll continue to do so. We've seen that there's consistent improvement among titles in the Translation Database, but as Chad Post has been reiterating the past few weeks, there are still issues. I explained in my last post that I decided on a different methodology this year, opting out of using the Translation Database in favor of reviewing select publisher catalogs myself. In this way, I hope to include a wider range of genres, categorizations, and books overall, specifically kidlit, nonfiction, and previously published titles. And so the best way to look at the latter two categories is to analyze what's going on in university presses.

Fifteen percent.

Academic presses are important for a lot of reasons, but it's important to remember why this stings a bit more than most of the other low-rated publishers: Academic presses carry with them a degree of prestige, canonization, and clout. Having so few works by women writers and even fewer works by women writers from around the world merely perpetuates our existing (flawed) assumptions about academia, women, and women's contributions to culture and science. Women have been contributing to the canon for literally the entire span of human history... why is this still erased? It's like another publisher - Penguin Classics - which published exactly zero works by women writers in translation this past year (versus four by men in translation). There are countless classic and modern works by women writers from around the world that deserve our attention and scholarship. We're still not there.

We have a long road ahead of us with many different problems to tackle. As the rates of women in translation steadily rise for fiction and poetry and as women in translation begin to receive the recognition they deserve in the English-language world (for example, the recent Man Booker International shortlist!), we can turn our attention to other matters. Why are there still so few children's stories in translation? Why is nonfiction in translation as dominated by men writers as it is? What's going on in other languages? Some of these are question we can't answer quite yet or still don't have solutions for.

But some of these questions we can begin to answer. Stay tuned...

Monday, August 19, 2019

WITMonth Day 19 | Awu's Story by Justine Mintsa | Review

For a book that's not even 100 pages long, Justine Mintsa's Awu's Story has a surprisingly long introduction. Clocking in at 24 pages (not including references), the University of Nebraska Press translation into English solidly leans into the idea that a short story can have a major impact. Unfortunately, like the introductions to many modern (and not-so-modern...) classics, translator Cheryl Toman's extensive (and fascinating) introduction also tackled some of the plot points in the book. Luckily, I've already learned to merely skim introductions for author-specific information and only read it fully after finishing the book itself. I advise other readers who prefer to go into the story with a clear mind to do the same.

And oh boy, do I advise readers get their hands on this book. Slim, yes, but Awu's Story packs major punch in such a brief space. The writing style is simple throughout, very direct and clear-eyed. Pieces of the story that feel unaddressed are almost all addressed more fully later. The book tackles huge subject matters, from ordinary village life, to family relationships, to love, to child pregnancy, to grief, to tradition... yet none of these feels out of place or dominant. With the exception of a single, somewhat rushed "payoff" scene near the end, the book largely feels like it earns its emotional beats.

To be honest? I kind of loved Awu's Story.

I mean, I guess I shouldn't sound so surprised or dismissive. There's nothing in Awu's Story's marketing or framing to suggest I shouldn't love it. On the other hand, there also isn't much to suggest it would hit me much beyond "oh this is a good book". Except Awu's Story really does end up feeling different, both in terms of my outsider view of Gabonese culture (of which, as you can imagine, I have limited exposure to) and just from a literary perspective. I have a mixed relationship with very simply written books, sometimes loving them and sometimes Awu's Story fell on the right side of that balance. The simplicity translated into straight-forward storytelling. The book progresses in a linear fashion; events happen one after the other and are cleanly described. The language is, by and large, direct. The one thing that bothered me a little bit was the dissonance between an older-style simplicity and occasionally very modern language (use of words like "hey" or "guy" in contexts that sometimes felt a little whiplash-y), but this too may have something to do with my expectations. It's also not really the point.

Awu's Story has a clear, progressing story, but it's hard to characterize this as a plot-based book. It is, as the English title implies, simply Awu's story, following life from early marriage through to middle age. It is, to a large extent, a feminist story with several characters breaking with traditional gender expectations within the story (Awu included). Its overarching themes and messages are definitely present and not particularly quiet, but they also still feel somewhat in the background. It's a book that feels natural in a lot of different ways. And I really did just love it. It's a short read that feels totally rewarding and enlightening and narratively satisfying. No, this is not a particular cheerful book in parts and I definitely cried a little bit by the end, but it's lovely and powerful and I hope that a lot more readers get the chance to read this. Awu's Story is far from one of the more popular, mainstream books you're likely to get a chance to read, but... you should. Highly recommended.

And oh boy, do I advise readers get their hands on this book. Slim, yes, but Awu's Story packs major punch in such a brief space. The writing style is simple throughout, very direct and clear-eyed. Pieces of the story that feel unaddressed are almost all addressed more fully later. The book tackles huge subject matters, from ordinary village life, to family relationships, to love, to child pregnancy, to grief, to tradition... yet none of these feels out of place or dominant. With the exception of a single, somewhat rushed "payoff" scene near the end, the book largely feels like it earns its emotional beats.

To be honest? I kind of loved Awu's Story.

I mean, I guess I shouldn't sound so surprised or dismissive. There's nothing in Awu's Story's marketing or framing to suggest I shouldn't love it. On the other hand, there also isn't much to suggest it would hit me much beyond "oh this is a good book". Except Awu's Story really does end up feeling different, both in terms of my outsider view of Gabonese culture (of which, as you can imagine, I have limited exposure to) and just from a literary perspective. I have a mixed relationship with very simply written books, sometimes loving them and sometimes Awu's Story fell on the right side of that balance. The simplicity translated into straight-forward storytelling. The book progresses in a linear fashion; events happen one after the other and are cleanly described. The language is, by and large, direct. The one thing that bothered me a little bit was the dissonance between an older-style simplicity and occasionally very modern language (use of words like "hey" or "guy" in contexts that sometimes felt a little whiplash-y), but this too may have something to do with my expectations. It's also not really the point.

Awu's Story has a clear, progressing story, but it's hard to characterize this as a plot-based book. It is, as the English title implies, simply Awu's story, following life from early marriage through to middle age. It is, to a large extent, a feminist story with several characters breaking with traditional gender expectations within the story (Awu included). Its overarching themes and messages are definitely present and not particularly quiet, but they also still feel somewhat in the background. It's a book that feels natural in a lot of different ways. And I really did just love it. It's a short read that feels totally rewarding and enlightening and narratively satisfying. No, this is not a particular cheerful book in parts and I definitely cried a little bit by the end, but it's lovely and powerful and I hope that a lot more readers get the chance to read this. Awu's Story is far from one of the more popular, mainstream books you're likely to get a chance to read, but... you should. Highly recommended.

Sunday, August 18, 2019

WITMonth Day 18 | Down with the Anglo-archy!

The 50 Day Countdown (part 3)

In my last post, I talked about how I felt the 50 Day Countdown list really showed the breadth of women writers in translation from around the world. But I hedged and hesitated, hovering around the topic that I really wanted to point out and that is... overall, the list is extraordinary wide-ranging with one major exception: Very intentionally, there is not one white European author on the list.There have been plenty of lists in recent years focusing specifically on women of color or women from particular regions. In fact, it's become a movement in its own right and justifiably so - the same marginalization that keeps women writers outside of mainstream recognition in the literary world applies doubly so for women of color. And yet whatever the effort needed to get English-language women of color in the public view, it is almost exponentially more difficult for women in translation, and so on. If we were to imagine a Venn diagram of the intersectional struggle, we'd see that we're left with a tiny overlap.

That the 50 Day Countdown is entirely comprised of women of color is not by accident; it is carefully deliberate. (Note: The term "women of color" is often problematic in an international context, as I'll discuss a bit more below.) I kept a close eye on people who shared the list to see whether anyone commented on the fact that it is entirely comprised of women of color. With the exception of one reader who expressed delight at the list's diversity, no one made any explicit mention. And wouldn't people say that's such a good sign? Look, here's a list of 50 women writers in translation that just so happen to all be women of color! When on day 49, I invited readers to suggest women they might like to see on day 50, a few recommended white European authors - it seems that the list's quiet revolution was subtle enough that it didn't even occur to those readers that their recommendation might be out of place.

As most of you probably know, I have a longstanding frustration at the general attitude toward translation as something niche or secondary. Take this list of African women writers as an example - the overwhelming majority are English-language writers, for absolutely no reason rooted in the reality of the continent's native languages. Resources by English-language readers or scholars almost always include books by exclusively Anglo-American/English-language authors. The women in translation movement is still on the outskirts of feminism and indeed, it largely seems to reside within the translation movement, rather than the feminist movement! This is something I've complained about before in many different ways.

My frustration is a muddled mess of emotions. I recognize that it's a good thing that people can skim through the 50 Day Countdown list and not be too surprised by how many different backgrounds they're encountering. Many readers, in fact, have commented on how they felt that the list introduced them to writers from countries they didn't expect, or that the list itself was impressive, or whatever. It's a mark of how far we've come that the race/ethnicity/backgrounds of these writers is not the only important thing about it, rather that these are remarkable, talented, award-winning, different, and interesting women writers who just so happen to be from all over the world.

But it doesn't feel like a good thing that the list again went ignored by those (very loud) voices who claim to support "diversity" the most. Diversity is a word that divides many and for good reason - human beings, after all, are simply human beings, not diverse. The way that we have this conversation is already tainted. I always recall Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's sharp observations in Americanah about what it means to be a non-American-black within a culture that automatically conflates blackness with certain cultural expectations (i.e. African-American culture). Similar to discussions in Americanah over immigrant identity in the US, my dissatisfaction with the phrase "women of color" in an international context comes into play. When your country is comprised of black people, you are not black as an identifying feature, nor are you a "woman of color". The phrase is one that is defined by white-dominant countries and cannot apply in the same way to non-white-dominant countries. Racial, religious, and cultural discussions are all entirely unique within the borders of different countries, and the fact that Anglo-American readers often gloss over these differences in the name of so-called progressive inclusiveness is to no one's benefit.

But just because diversity is a phrase that is context-dependent doesn't mean that it's not something we ought to discuss. From an Anglo-American perspective, it is important to point to writers of "diverse" origins, which is precisely what the 50 Day Countdown list did. When we discuss "literature in translation" we're already assuming an English-language bias and cultural context, which means that there is little excuse for Anglo-American-based diversity movements to continue to ignore women in translation.

So what is the purpose of this post? Am I just complaining about not getting the attention that I wanted? Well, yes, to a certain degree. Mostly, though, I find myself exhausted by the hypocrisy of a movement that doesn't pay any attention to something if it's not blatant. Would the list have gained more traction if I explicitly framed it as "50 WOC You Have to Read!"? Is there some magic trick that we need in order for most Anglo-American feminist readers to recognize their Anglo-centrism? I'm tired of having to fight for WITMonth to have a seat at the table. I'm tired of having to fight for mainstream feminist groups and movements and voices to notice. To use an example of a white woman whose intersectional feminism does include many women of varying backgrounds, Emma Watson's Our Shared Shelf book club still has, by my count, only one book by a woman writer in translation (out of 27). The erasure happens everywhere, every day.

As I've argued a hundred times before, women in translation should not be niche. They should not be bonuses. They should not be the rarity that crops up one month a year, and even that's just a drop in the bucket compared to all the other books everyone is reading in August. The 50 Day Countdown shows that it's possible to make a list of 50 women writers from around the world, without country repeats; the 100 Best WIT nomination list shows that it's possible to read hundreds of books from around the world with strong endorsements for every single title. While the women in translation movement exists due to a relative imbalance, I will repeat what I've said since 2014: There is no lack of women writers in translation, but we do have to put in the work to find them. This is true for established readers of literature in translation and it's true for new readers of literature in translation and it's true for feminist readers who have never considered translation as an intersection worth exploring.

Let's get the word out in feminist circles: The era of English-only diversity is over.

Saturday, August 17, 2019

WITMonth Day 17 | Flights by Olga Tokarczuk | Review

I waited a long time to read Flights. Despite having had multiple translations of her books into English prior to Flights, this was the book that brought Olga Tokarczuk to my sphere of awareness. Everyone seemed to be reading Flights last year; it was a WITMonth hit, people were praising Tokarczuk and translator Jennifer Croft from all directions, and ultimately the book went on to win the 2018 Man Booker International Prize (and was shortlisted for both the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation and the National Book Award for Translated Literature). Flights has been... everywhere.

I waited a long time to read Flights. Not because I thought I wouldn't like it (though I won't pretend there wasn't some of my usual concern that I'd end up disappointed by a book that everyone else seems to have loved!). Not because I didn't want to read it (I very much did). And not because I couldn't get my hands on it (I lovingly passed my fingers over its cover when I was in London this past November). No, I waited a long time because the moment I saw this bright yellow hardcover for the US edition, I knew I wanted this version. I wanted a spine that would crackle under my fingers. I wanted a bright, bold cover. Forgive me, but the UK Fitzcarraldo blue just really does not do it for me.

And so I waited. I waited to begin my travels. I waited as I traveled through Fitzcarraldo-friendly lands. I waited as I arrived in the US and was exiled to the bookstore-deprived suburbs of Central New Jersey. (I mean... "was happily spending time with my family". *cough*) I waited as I placed online orders for several other books. I waited until I walked into a bookstore that had Flights on full display, and then I hugged the gorgeous hardcover to my chest. Flights boarded my flight home, carefully tucked into my backpack between my laptop and extra scarf. (And six other books. Let's not get into it...)

I began reading Flights on my last flight home. Three months of flying all across the world (16 flights in total...), traveling to new countries and continents, seeing new sights, meeting new people, exploring new experiences. At first, the book felt like it would be a slow burn - the shifts in style, narration, and literal stories kept throwing me off. How much of Flights was a novel? How much was short stories? How much was autobiography? The book seemed to progress with its own unique rhythm, sometimes working for me, sometimes less. I read slowly, steadily - first on my flight, then through my jetlag, and then bits and pieces every night before bed.

And then I began to read voraciously. Somewhere around the halfway mark, I felt something shift inside me; I suddenly felt like the book was pulsing with life, vibrating in my hands. I began to feel how the stories fit together. It suddenly clicked.

One story lingers, that of the (implied) New Zealand scientist who heads back to Poland to visit a dying friend. I kept feeling that the story was written for me, having just come back from my own travels throughout New Zealand and contemplating all sorts of bigger life questions (though obviously not as big as those in the story, for those who have read it). The story was one that suddenly had an additional dimension by virtue of the fact that I had waited - could the story have meant nearly as much to me before having traveled throughout New Zealand? (No.) Pieces of it seemed to fit perfectly into the tapestry of my jumbled emotional puzzle.

I ultimately loved Flights. I loved how the experimental, "weird" side ultimately ends up paying off. I loved how the book feels like it's growing as you're reading it. I loved the clarity of the writing (and translation!). I loved its unique voice, at once intimate and technical. I loved how it was quite unlike any of the other books I had read recently. I loved how it managed to be exactly what I needed at exactly the right time.

I waited just long enough to read Flights.

I waited a long time to read Flights. Not because I thought I wouldn't like it (though I won't pretend there wasn't some of my usual concern that I'd end up disappointed by a book that everyone else seems to have loved!). Not because I didn't want to read it (I very much did). And not because I couldn't get my hands on it (I lovingly passed my fingers over its cover when I was in London this past November). No, I waited a long time because the moment I saw this bright yellow hardcover for the US edition, I knew I wanted this version. I wanted a spine that would crackle under my fingers. I wanted a bright, bold cover. Forgive me, but the UK Fitzcarraldo blue just really does not do it for me.

And so I waited. I waited to begin my travels. I waited as I traveled through Fitzcarraldo-friendly lands. I waited as I arrived in the US and was exiled to the bookstore-deprived suburbs of Central New Jersey. (I mean... "was happily spending time with my family". *cough*) I waited as I placed online orders for several other books. I waited until I walked into a bookstore that had Flights on full display, and then I hugged the gorgeous hardcover to my chest. Flights boarded my flight home, carefully tucked into my backpack between my laptop and extra scarf. (And six other books. Let's not get into it...)

I began reading Flights on my last flight home. Three months of flying all across the world (16 flights in total...), traveling to new countries and continents, seeing new sights, meeting new people, exploring new experiences. At first, the book felt like it would be a slow burn - the shifts in style, narration, and literal stories kept throwing me off. How much of Flights was a novel? How much was short stories? How much was autobiography? The book seemed to progress with its own unique rhythm, sometimes working for me, sometimes less. I read slowly, steadily - first on my flight, then through my jetlag, and then bits and pieces every night before bed.

And then I began to read voraciously. Somewhere around the halfway mark, I felt something shift inside me; I suddenly felt like the book was pulsing with life, vibrating in my hands. I began to feel how the stories fit together. It suddenly clicked.

One story lingers, that of the (implied) New Zealand scientist who heads back to Poland to visit a dying friend. I kept feeling that the story was written for me, having just come back from my own travels throughout New Zealand and contemplating all sorts of bigger life questions (though obviously not as big as those in the story, for those who have read it). The story was one that suddenly had an additional dimension by virtue of the fact that I had waited - could the story have meant nearly as much to me before having traveled throughout New Zealand? (No.) Pieces of it seemed to fit perfectly into the tapestry of my jumbled emotional puzzle.

I ultimately loved Flights. I loved how the experimental, "weird" side ultimately ends up paying off. I loved how the book feels like it's growing as you're reading it. I loved the clarity of the writing (and translation!). I loved its unique voice, at once intimate and technical. I loved how it was quite unlike any of the other books I had read recently. I loved how it managed to be exactly what I needed at exactly the right time.

I waited just long enough to read Flights.

Friday, August 16, 2019

WITMonth Day 16 | #100BestWIT deadline approaching!

This is just a reminder that the #100BestWIT submission deadline - AUGUST 25TH - is fast approaching! Don't forget to send in up to 10 nominations of books by women writers from around the world (writing in any language other than English, whether or not it's been translated into other languages). Send your nominations via Twitter (@read_WIT), Instagram (@readwit), comment here, or email (biblibio [at] gmail)! As of right now, there are almost 1000 individual votes, but we can definitely get more and have a more decisive canon. So spread the word - on social media, among your friends, online and offline - and send your nominations in!

Thursday, August 15, 2019

WITMonth Day 15 | "Lives of Three Generations of Bedouin Women" by Nuzha Allassad-Alhuzail | Review

You know how I often say that I feel "unqualified" to write reviews of certain books? Sometimes that's because a book just isn't to my taste and I don't feel that I can adequately speak for readers to whom the book is geared. Sometimes it's because the book involves literary references that I'll never be able to place. Sometimes it's because the book is on a topic that is far beyond my scope of experiences/knowledge, and I just have to trust the writer.

This review falls into this latter category.