The problem is that despite all of the good, we've still got a lot of bad. It's not just an individual publisher matter, either. There's a systemic problem when you start to look at publishers who define themselves in certain ways, those who engage with WITMonth, and those who distance themselves from it.

Take Archipelago Books. This is a publisher I've been tracking for years, with the knowledge that they're one of the yearly disappointments. And so I was not particularly surprised by what I got: Archipelago sits at an 18% publishing rate of women writers in 2019. Year after year, Archipelago has proven to be one of the least WIT-friendly publishers. Considering how many of my favorite works by women in translation have been put out by them, it's disheartening that they don't seem to be making any effort whatsoever to balance out their catalog.

But, I reassured myself, they also have a children's literature imprint! Archipelago: Elsewhere Editions is an imprint devoted to international, quality literature for children. We all know, of course, of the "industry bias" towards women in children's literature, right? (...right?) Imagine my surprise, then, when it turned out that all 4 books published by this imprint in 2019 were books by men. That puts women in translation at 13% between the combined catalogs. That is... honestly inexcusable. When I reached out for comment, the response was a friendly reassurance that the publishers are aware of the imbalance and seeking to correct it, alongside a list of recent and forthcoming releases. My policy has been, until now, to give publishers the benefit of the doubt when they express an interest in improving things. I hope that next year I'll be able to add Archipelago to the list of publishers on the rise.

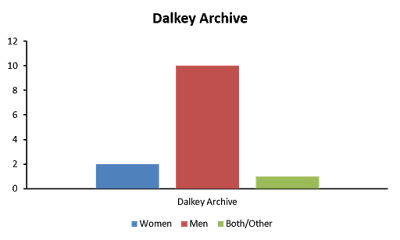

Dalkey is another eternal disappointment. Despite not having a publicly available catalog, I collected publication data from Amazon (seriously, that's all I could think of...) and was distinctly unsurprised to count 2 books by women in translation (alongside one mixed anthology), compared to 10 by men. How sad is it that 23% is still fairly good for Dalkey? Let's move on...

It's the last category that I want to talk about the most, though. We've already discussed how things are getting better among literary publishers, and my hope is that they'll continue to do so. We've seen that there's consistent improvement among titles in the Translation Database, but as Chad Post has been reiterating the past few weeks, there are still issues. I explained in my last post that I decided on a different methodology this year, opting out of using the Translation Database in favor of reviewing select publisher catalogs myself. In this way, I hope to include a wider range of genres, categorizations, and books overall, specifically kidlit, nonfiction, and previously published titles. And so the best way to look at the latter two categories is to analyze what's going on in university presses.

Fifteen percent.

Academic presses are important for a lot of reasons, but it's important to remember why this stings a bit more than most of the other low-rated publishers: Academic presses carry with them a degree of prestige, canonization, and clout. Having so few works by women writers and even fewer works by women writers from around the world merely perpetuates our existing (flawed) assumptions about academia, women, and women's contributions to culture and science. Women have been contributing to the canon for literally the entire span of human history... why is this still erased? It's like another publisher - Penguin Classics - which published exactly zero works by women writers in translation this past year (versus four by men in translation). There are countless classic and modern works by women writers from around the world that deserve our attention and scholarship. We're still not there.

We have a long road ahead of us with many different problems to tackle. As the rates of women in translation steadily rise for fiction and poetry and as women in translation begin to receive the recognition they deserve in the English-language world (for example, the recent Man Booker International shortlist!), we can turn our attention to other matters. Why are there still so few children's stories in translation? Why is nonfiction in translation as dominated by men writers as it is? What's going on in other languages? Some of these are question we can't answer quite yet or still don't have solutions for.

But some of these questions we can begin to answer. Stay tuned...

No comments:

Post a Comment

Anonymous comments have been disabled due to an increase in spam. Sorry!