Read parts 1 and 2

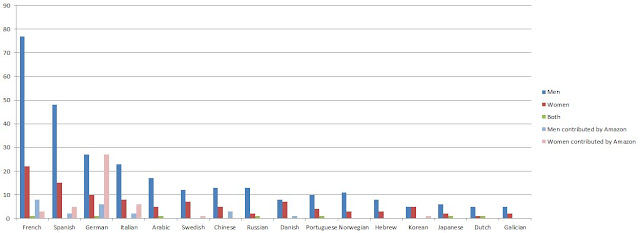

After a longer than intended break, we're back with the latest round of women in translation statistics. This set of stats aims to debunk a few more pervasive and utterly false claims regarding the global lack of women writers in translation, and also points to an area in which we can absolutely do better.

Methodology

As always, my work is based on the US-centric

Three Percent database (heavily expanded in this case...), and thus only includes first-time translations of fiction and poetry titles. Genre and original publication year were determined on a title-by-title basis.

Original publication year was largely assessed through Goodreads data, however in many cases the provided year was inaccurate and further research was required. This means that the margin of human error (though uncalculated) is likely to be

much higher for publication year than for other metrics, and it is entirely possible that older titles or posthumously published titles were given misleading years. Most publication years, however, were verified through copyright information and Wikipedia, suggesting that at the very least, the data should be ballpark representative.

Genre definitions were given by my own assessment of the title's summary, including several overlapping categories (crime, thriller, mystery, etc.) and reductionist labels. By and large, any title

marketed as "genre" was given the marketed label (thriller, romance, mystery etc.), while only titles which were

explicitly of a genre nature were labeled (fantasy, sci-fi, historical fiction, etc. for ambiguously marketed titles with obvious subject matters). While this too is an imperfect metric, it nonetheless captures the broader picture and should be largely representative given the sample size.

Genre

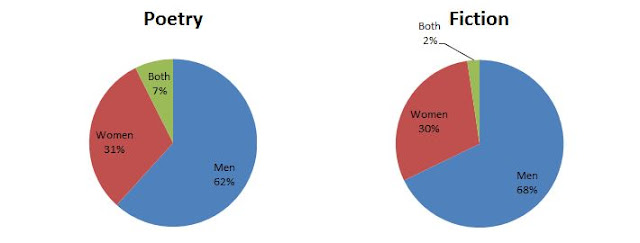

The Three Percent database provides two genres: fiction and poetry. While I've found this division hypothetically interesting in the past, the results boil down simply:

Basically: there is no significant change from the overall stats. Good to know! We can suggest from this data that women are

slightly more likely to be published for writing poetry than fiction, but the difference is fairly minor.

This is all I'd ever looked at in previous years, but this time I decided to follow a hunch and do some more digging. As I described in the methodology section, I went through the database title-by-title and gave fairly generic genre descriptors: fiction, crime, thrillers, romance, sci-fi, fantasy, poetry, etc. As you can tell, these definitions are far from comprehensive or indeed unique. The idea wasn't to specifically pinpoint the genre of each title (such a task is frankly

impossible), but to get an impression of what sorts of books are being translated into English.

Which means the first chart I'm going to show you ostensibly has nothing to do with women in translation:

From a general lumping-together of all "non-literary" genres versus "literary fiction" (with short stories cast as a separate category since collections may yet contain more than one genre and often include more than one writer), it's apparent that the world of literary translations is actually pretty evenly balanced between so-called "genre" fiction, and "literary" fiction.

This may seem like a random, quirky tidbit, but it's quite a bit more than that. Another of the most common comebacks to the standard ~30% translation rate for women writers is the claim that literature in translation is usually

literature, and women are "just more likely to write

genre"

(this is a claim that's cropped up in comments, tweets and private conversations, often with

publishers). The above chart disproves the first part of that claim. The next will disprove the second:

As you can see, the gender breakdown here is not all that different from the global one. Yes, women are

slightly better represented in genre fiction than overall, but four percentage points is... not all that much. It's a difference of 11 books out of over 200 in the "genre" category. Certainly nothing compared to the "dominance" women allegedly have in genre fiction. This is almost identical to the ratio we see pretty much everywhere, and the excuse of "genre" stumbles once it's established that genre in fact makes up just under half of all fiction/non-poetry publications in translation.

This myth is important to bust for several reasons. First: The implication of a two-tiered quality ranking. Linking women writers to "genre" (often disparagingly, with outright statements of the lower quality) is no different than the old argument that "

women just don't write as well". It's an attempt to discredit works written by women, as well as an obvious move to

separate them somehow from a

standard (which is inherently defined by men).

Second: It is simply

false. Women, it's true, write a fair amount of fiction (of all sorts), but this is not translated (!) into translations. Let's just say for a moment that women

were writing far more genre fiction than men (and it's entirely possible that they

do; I genuinely do not know global publishing trends). That means that men - despite being a minority in their native languages - would be getting published at

significantly prioritized rates than women!

Here I'll also bust another myth: AmazonCrossing's strength as a publisher of women writers

does not simply rely on genre. While they

are predominantly a publisher of genre fiction (66/75 titles), women make up 6 of their 9 purely fiction ("literary") titles. Another predominantly genre publisher, Atria, also see 2 out of its 3 non-genre titles as written by women. It's a trend that holds, and in fact with the exception of AmazonCrossing (always the exception), publishers that focus on genre fiction publish

far fewer women writers than others! Below is a chart showing genre books by publishers (of more than two books in 2015) with majority "genre" titles (in percentages):

Not so women-dominated after all. Once again, AmazonCrossing carries most of the weight.

Original year of publication

The next metric - also new, and now specifically focused on fiction titles - stems from another set of hunches. Before I begin, I should note that I began collecting data with an idea in mind as to what the bias would be, and discovered that I was wrong. I initially expected to see a short delay when it comes to translating contemporary books by women writers, but soon found that there was no clear difference. I also noticed that some books had pretty significant gaps between when they were

translated and when they were published

in the US. I dropped this categorization while analyzing the data, because my initial hypothesis proved incorrect. I have to admit: I'm glad to know women writers don't face a clear delay when it comes to recent publications.

That said.

I divided the data into three time periods. The first was 2010-2015 and - as noted - there was no significant difference in terms of publication rates (for fiction

or genre). On the contrary: women made up 36% of publications in that time period, somewhat pushed by the prevalence of recently released genre novels by both men and women.

The second was 1971-2009. Here a gap begins to open just a bit overall: 27% women writers. Once I looked

only at "fiction" titles, however, the gap opened further, and women made up only 23%. So there is clearly some struggle in translating women's backlog literature.

The third time frame was pre-1971. This cutoff was effectively to create some sort of "classics" division, with 1970 chosen in large part because it's been 45 years, and I'm young enough that I genuinely view that as a long time ago (sorry if this makes anyone feel old! I promise it's intentional!). This division made me stop in my tracks and stare at the data for a long, long time. I'd had a hunch that women would be severely under-represented in the "classics" realm (despite these being, of course, first time translations), but that could not prepare me for the

scope of the imbalance.

You see, of 38 titles I identified as having been published before 1970 (including short story collections I could solidly identify as predominantly of the era, such as Clarice Lispector's complete stories and poetry collections, here reintroduced),

4 were written by women. To put that in chart form:

This metric is

unbelievably infuriating. One of my focuses during the 2015 women in translation month was classic titles, and I unsurprisingly struggled somewhat to find books, even more when seeking books which have been incorporated into the "canon". Meanwhile, I discovered a practical treasure-trove of

untranslated works (including a plethora of explicitly feminist literature). True, not all would fall under the category of "fiction", but there's definitely

a lot out there that's never been translated.

And there's the part that fills me with rage. The Three Percent database, I'll again note, only includes

first-time translations. You won't find a new translation of

War and Peace here. Sometimes there's a new collection of short stories by a famous author (in this year's example, a new collection of Chekhov works) which qualifies, but these are largely little-known writers and utterly unknown "rediscovered masterpieces". So why are they almost all by men? Why is the

earliest book by a woman writer only from 1921, while men have 7 books from the 19th century and 1 from the 17th?

I can hear the arguments already: "But women didn't used to write as much as men!" You know what? Sure. Sure,

let's say you're right, and only 10% of all pre-1970 literature was written by women. Why in the world should that impact which books we choose to translate and

rediscover in 2016? These are not established books. With the exception of one book,

none of these books were written by famous men, or men who left a lasting impact on literature.

They are already unknowns. And I find myself wondering: why not take that opportunity in promoting an unknown writer and recognize the literally thousands of women writers history has almost

purposely forgotten? We know an imbalance exists, has existed, and seems determined to continue to exist. Is this not an opportunity to right the wrongs? Is this not

the opportunity to bring to light literally hundreds of regarded, important and historically relevant texts by women writers from around the world?

The utter lack of books for kids/YA

This one doesn't even need a chart. Out of 549 titles in the 2015 database, two were fairy tale collections and three were marketed towards young adults (though here I may have missed a title or two; we're still talking about 1-2% at most). Such a huge hole made me wonder if there wasn't something else hiding here or a problem with the source data.

I tweeted Chad Post about this imbalance and he explained that he does not include picture books in the database. This explains the glaring children's books gap, but not the lack of YA. Young adult and children's literature has been going through a targeted diversification process, with movements like "Diversify YA" and "We Need Diverse Books" leading the charge. It's critical that those efforts do not forget the importance of international and translated fiction, especially given the increasing tendency towards xenophobia in Anglo society. For literature in translation to cease being niche, it must be viewed as entirely normal by younger readers as well.

How does this relate to women in translation? On the one hand, it doesn't. This is simply another field in which a stark and deeply problematic imbalance is present. On the other hand, women writers are often credited with writing more books for kids and according to

VIDA's Children's Literature count from 2014, women are

generally more likely to win awards for children's books (indicating that perhaps women

do write a majority of literature for children, especially if we assume the bias against women when awarding prizes crosses genres as well). While I cannot say for certain if this true worldwide, it may act as an indicator or guidepost that is without a doubt relevant to our overall conversation.

The emerging picture

A good deal of what I've tried to do with the women in translation project (and these stats posts) is identify various misconceptions that surround the lack of women writers in translation, as well as try to find the source of the problem. These posts can only ever look at that which is available in English and in that regard will forever be incomplete.

That doesn't mean they can't be representative of

something. Yes, it means something when publishers year after year after year publish 30, 20, 10, 5% women writers. Yes, it means something when the problem stems not from one pin-pointed mark on the map, but across the entire globe. Yes, it means something when the problem spans genres and eras. The picture reveals a stubbornly

consistent lack of women writers in translation, regardless of the metric thrown at the problem. This is deeply troubling.

Is there a single entity to blame? No. This is a problem that literally spans continents, centuries and concepts. It's a problem we'll only be able to solve by working together across borders and languages and ideas.

And to solve it, we need to know what we're up against. This is just another piece of that endlessly complex puzzle.

These questions hurt not because there's something wrong in them. On the contrary. These are exactly the questions that need to be asked. No, what saddens me is that I've done a poor job in expressing the need for intersectionality. Because here's the thing: a project like women in translation cannot exist without intersectionality. It is meaningless without intersectionality.

These questions hurt not because there's something wrong in them. On the contrary. These are exactly the questions that need to be asked. No, what saddens me is that I've done a poor job in expressing the need for intersectionality. Because here's the thing: a project like women in translation cannot exist without intersectionality. It is meaningless without intersectionality.