(NOTE: An English summary of this data will be shared in a separate post.)

"חודש נשים בתרגום"

"נשים בתרגום" זה לא מושג מוכר בישראל, ואפשר להבין למה.

מה משמעות המושג הזה? למה הכוונה? האם מתייחס לנשים בתוכן הסיפור? סופרות? מתרגמות? ומה עם סופרות א-בינריות?

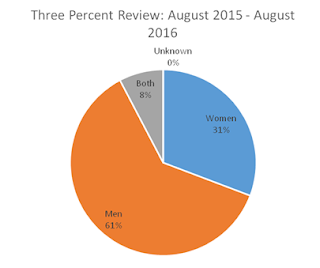

"נשים בתרגום" מתאר ספרות מתורגמת שנכתבה במקור על ידי נשים. המושג מגיע מאנגלית, Women in Translation, בעקבות מחקרים שנעשו על תרגומים ספרותיים שהראו כי נשים מהוות רק כ-30% מכלל התרגומים החדשים לאנגלית של ספרות יפה ושירה. כשמוסיפים תרגומי ספרי עיון, קלאסיקות, וספרות ילדים/נוער, אחוז הסופרות יורד לכ-25%. אך המושג "נשים בתרגום" אינו משקף את כל הסיפור.

קודם כל, בהמשך לטעות הנפוצה: ״נשים בתרגום״ מתייחס לסופרות, לא למתרגמות. עבודת התרגום היא אכן עבודה מאתגרת במיוחד, אך כוונת הפרויקט היא למשוך את תשומת הלב לקולן של הסופרות וסיפוריהן.

בנוסף, לא מדובר רק בנשים! "נשים בתרגום" גם מעודד ומפרסם ספרות מאת סופרים/ות א-בינאריים/ות או סופרים טרנסים שבוחרים להכלל.

ולבסוף, כשאנחנו מדברים על ״נשים בתרגום״ בהקשר הישראלי, אנחנו לא באמת מדברים על תרגומים מכל השפות באופן שווה. כי בעצם - הכוונה היא דווקא לספרות שמתורגמת משפות שאינן אנגלית.

אז מהו בעצם חודש נשים בתרגום? כל שנה במהלך חודש אוגוסט אנחנו מכירים, מפרסמים וחוגגים את הספרות הנפלאה הזו.

(הערת אגב: אמנם אני יזמתי את הפרויקט בראשיתו, ואני כמובן דוברת עברית, אך המושג ״נשים בתרגום״ ראה אור לראשונה בעברית בבלוגים ספרותיים שהגיעו לפרויקט דרך קהילת הספרות דוברת האנגלית, לא דרכי!)

בשנה שעברה, התראיינתי אצל דפנה לוי במוסף הספרותי "המוסך". זו הייתה בעיניי אחת השיחות המעניינות ביותר בנושא נשים בתרגום שהשתתפתי בהן, ולא רק כי סוף סוף הייתה לי הזדמנות לדבר גם על נושאים הקשורים לישראל באופן ספציפי, אלא שהכתבה מהווה מבוא מקיף ומעמיק לכל פרויקט ״נשים בתרגום״ בשנים האחרונות.

עכשיו הגיע הזמן לדבר על המצב בישראל.

אנשים בארץ בדרך כלל מצביעים על הצלחתן של מספר מצומצם של סופרות דוברות אנגלית כסימן לכך שפרויקט "נשים בתרגום" חסר משמעות. "תראי עד כמה ג'יי קיי רולינג מוצלחת! מה פתאום צריך חודש נשים בתרגום?" (וכן, זו תמיד הדוגמא...) אמירות כאלה מפספסות את מהות הפרויקט.

נחזור רגע להגדרת נשים בתרגום בהקשר של ספרות מתורגמת לאנגלית. אצל קוראים דוברי אנגלית ישנה נטייה לקרוא מעט מאוד ספרות מתורגמת, והמעט שיוצא לאור אינו זוכה לקהל רחב. אבל בהקשר העברי, ערבי, לטבי, סיני, אינדונזי, מלאיאלאם, לא-משנה-באיזה-שפה-מדברים-חוץ-מאנגלית, יש פער עצום כשבוחנים את שפת המקור של הספרות המתורגמת. נכון, בעברית יש מלא תרגומים... אך כמעט כולם מאנגלית.

בהחלט צריך להתייחס לפערים מגדריים ותרבותיים בספרות שמתורגמת מאנגלית. לא סתם קיימים באנגלית ארגונים שלמים לקידום סופרות (למשל, VIDA או ReadWomen) וכמובן שיש גם פערים אחרים, למשל בקידום סופרים/ות שחורים/ות, ספרות מהגרים, ספרות עמים ילידים, ספרות מעמד פועלים, ספרות קווירית וכו'. ובכל זאת.

כמה ספרות מתורגמת באמת קיימת בעברית?

בשנה שעברה, אספתי מידע לגבי כל הפרסומים של מספר הוצאות לאור בישראל: עם עובד, הספרייה החדשה, תשע נשמות, אחוזת בית, עליית גג, בבל, ו-כנרת, זמורה-ביתן, דביר.

הדבר הראשון שבולט לעין: לא חסרים תרגומים מאנגלית. להפך - תרגומים מאנגלית שולטים בשוק הישראלי. סך הכל, 41% מהספרים שיצאו לאור ב-2018 בהוצאות אלו נכתבו במקור בעברית, 41% נכתבו במקור באנגלית, ו-18% מכל שאר שפות העולם (כאשר ספר אחד - שנכתב במקור בקוריאנית - בעצם תורגם מהתרגום לאנגלית, לא מקוריאנית באופן ישיר). אם נתייחס לספרות מתורגמת כקבוצה עצמאית, אנגלית מייצגת 69% מכלל הספרות המתורגמת לעברית.

חשוב לציין כי במידה מסוימת בחרתי במוציאים לאור האלה כי ידעתי שהם מפרסמים "יותר" ספרות בינ"ל ולא רק תרגומים מאנגלית. בהוצאה הגדולה ביותר שבדקתי, שגם מאוד מייצגת את ה"מיינסטרים" הישראלי (כנרת, זמורה-ביתן, דביר), האחוזים דווקא נטו עוד יותר לכיוון תרגומים מאנגלית, כאשר 48% מכלל הספרים שיצאו לאור ב-2018 היו תרגומים מאנגלית, 44% ספרות מקור מעברית, ו-8% משאר שפות העולם.

הדומיננטיות של אנגלית בהקשר של תרגומים לעברית לא מפתיעה אך כן מאכזבת. ספרות אמורה לחשוף אותנו להשקפות עולם שונות, למצבים שונים, לסיפורים שונים. איך אנחנו אמורים להבין את העולם אם אנחנו כל הזמן נחשפים רק לארה"ב ואנגליה?

מה ההבדלים המגדריים?

נתחיל מהשאלה: כמה ספרים מאת נשים או גברים יוצאים לאור בישראל בכל שנה? מתוך מבחר המו"לים שבדקתי, ב-2018 מדובר בפער מפתיע: כ-57% מכל הספרים שיצאו לאור נכתבו על ידי גברים, 41% על ידי נשים, ו-2% ספרים שנכתבו על ידי גברים ונשים ביחד ("משולב"). לא ציפיתי להבדל כזה גדול - בעבר התרשמתי שהמצב בישראל מאוד שוויוני בין סופרות לסופרים. מאיפה הפער מגיע?

בחרתי לחלק את הנתונים לקבוצות. קודם כל, הסתכלתי אך ורק על ספרים שנכתבו במקור בעברית - שם הפער קטן יותר, כאשר 54% סופרים, 44% סופרות, ו-2% משולב. אחוזי התרגומים מאנגלית הם לפי אותה עקומה - 56% סופרים, 41% סופרות, 3% משולב. תרגומים מכל שאר השפות שאינן אנגלית נראו לגמרי אחרת. כאן, רק שליש (33%) מהספרים נכתבו על ידי נשים, כאשר 65% נכתבו על ידי גברים ו-2% משולב.

פערים קיימים גם בחתכים אחרים, כמו ז'אנר. הגדרתי כמה ז'אנרים כלליים כדי לנסות להבין אם יש פערים בין נושאים מסוימים... ואכן יש. ז'אנרים כמו ספרות ילדים, ספרות נוער, וסיפורת/ספרות יפה לרוב כללו אחוז גבוה יותר של סופרות (לדוגמא, נוער) או אחוזים מאוד דומים של סופרים וסופרות (ילדים וסיפורת), לפחות בעברית. כלומר מכיוון שרוב הספרים שיוצאים לאור בישראל שייכים לז'אנר ספרות יפה/סיפורת, לא מפתיע שתמיד חשתי שהמצב בעברית די שוויוני - 51% מסיפורת מקור נכתבה על ידי נשים.

אבל כן חשוב לשים לב לז'אנרים החריגים מבחינת פערים מגדריים, ספציפית עיון ושירה. שני הז'אנרים האלה מהווים עולם ומלואו בספרות מקור וספרות מתורגמת. בשירה למשל, רק 17% מהפרסומים הם מאת נשים (פירושו של דבר - ספר בודד); איך ייתכן כי ב-2018 נתון כזה מייצג את כל ספרי השירה מאת נשים ממבחר מו"לים מובילים בישראל? בעיון - הז'אנר השני בגודלו בישראל - רק 27% מהספרים נכתבו על ידי נשים. האמנם נשים באמת לא כותבות בז'אנרים האלה? או שאולי סתם פספסתי משהו? אלו שאלות להמשך.

אותה מגמה נראית גם בתרגומים מאנגלית, שם שוב קיים פער עצום בעיון (רק 16% סופרות, מתוך 25 ספרים סה״כ). בהתחשב במעמד של ספרי עיון (ביוגרפיה, היסטוריה, מדע פופולרי, ועוד), יש חשיבות חברתית מקיפה לפער המגדרי. המשמעות של צמצום פרסום סופרות היא שקוראים ישראלים אינם נחשפים להשקפות עולם שונות (שלא נדבר על זה שכמעט כל הספרים נכתבו על ידי גברים לבנים ולא משקפים את העולם דובר האנגלית בשום פנים ואופן).

מעודד לראות שלמרות המחסומים העומדים בפני סופרות דוברות אנגלית, הן דווקא מתורגמות לעברית במידה שוויונית. בהחלט דבר שצריך להתגאות בו. בנוסף, מעניין אך לא מפתיע לראות כי מעט ספרי הרומנטיקה שפורסמו נכתבו על ידי נשים. מצד שני, לא ברור למה כולם נכתבו במקור באנגלית.

המצב נהיה מעט הזוי כשמנתחים את הנתונים של שאר שפות העולם. למרות שקיימים ספרים מתורגמים בסוגי ז'אנרים שונים (כמו מתח, עיון, ושירה), ייצוג סופרות בז'אנרים אלה פשוט לא קיים. כפי שניתן לראות בטבלה בהמשך, יש מעט ספרים מתורגמים בסך הכל, אבל בכל זאת מדובר בפערים בולטים ובלתי נתפסים. והפער בז'אנר המוביל בתרגומים בינ"ל הוא לא פחות מרגיז - רק 35% מסיפורת מתורגמת מכלל שפות העולם שאינן אנגלית, נכתבו על ידי נשים.

|

פירוט מגדרי של כלל התרגומים משפות שאינן אנגלית

אני מאוד מקווה שנוכל ללמוד מהממצאים הנ"ל לגבי הפערים - גם מבחינת תרגומים משפות שונות וגם מבחינת מגדר - במטרה להרחיב את מגוון הספרים שיוצאים לאור בישראל מדי שנה. בסופו של דבר, נרצה שהנוף הספרותי שלנו ישקף את העולם שבו אנו חיים. יש כל כך הרבה ספרים מכל העולם, ובוודאי שגם המון, המון סופרות מוכשרות, מעניינות ומרגשות. העולם עצום ומדהים - למה שלא נחשף לכולו גם בעברית?