Wednesday, August 31, 2016

WITMonth Day 31 | All good things must (not) come to an end...

The 31st of August means that technically speaking, "Women in Translation Month" - WITMonth 2016 - has come to an end. And oh what an end.

This month has seen blog posts and reviews, recommendations and lists, interviews and stories, ideas and discussions, stats and comparisons, questions and answers, awareness and awareness and awareness.

Readers and translators from all over the world took part in some form or other, with discussions breaching the English language divide as well. Bookstores took part by hanging up WITMonth signs and displays. Translators promoted their works. Publishers offered discounts. Readers read.

If the purpose of WITMonth remains awareness - and it does - then August 2016 - WITMonth The Third - succeeded. That's the only word for it. Many readers who had never questioned their unconscious biases before now began to try to amend their own imbalanced reading. Readers who struggled to find Good-with-a-capital-G books by women in translation complained of overly long TBR lists. Bloggers discussed where WITMonth could go from here. Reviewers highlighted new and modern masterpieces.

These are victories. Clear, resounding victories. We have come together as a community and said this is a topic that needs discussing. We have pointed to worthy women writers and screamed listen to these brilliant writers. These are seemingly trivial steps, and yet they're critical for the project's continued success. They are critical for achieving the basic goals of parity and equality.

WITMonth itself is a sort of manifestation of the problem, with further isolation. However, readers are not meant to drop all their books by women in translation until next time, reading only men for the remaining eleven months of the year. On the contrary. I hope that readers will take these wonderfully expanded lists and TBR piles, and will just... continue.

Keep reading women in translation.

That's it. We know the problem exists. We have ideas as to the future. But right now the most important thing is that we continue. That we continue fighting for these too-often-ignored voices. That we continue reading those books which have been translated. That we continue to challenge the existing imbalances in translation (gender, sexuality, country of origin, etc.) and seek to fix them.

WITMonth 2016 has been beautiful and wonderful and so much more than I ever imagined it would be. But why must it be only one month?

Tuesday, August 30, 2016

WITMonth Day 30 | What have we read? A list!

A cheat post today as we edge closer to the end of WITMonth... Check out the excellent list compiled by @Lillie_Langtry on Twitter to see what people have been reading/reviewing this WITMonth! While the list is incomplete in parts (some of my own non-tweeted-out reads are missing, for example!), it's a great place to start when looking for great women in translation to read, now and in the future. Happy reading!

Monday, August 29, 2016

WITMonth Day 29 | Genres | A short interlude

WITMonth 2016 is almost over and there will be plenty of discussions to be had later as well, but before we go... a brief thought on genres. I love seeing all the books people have chosen to read for WITMonth and I love seeing how very different many of them are. But... I cannot help but notice how most of us have remained comfortably within the world of simple fiction.

I don't for a moment want to take away from those readers who have spent the past month championing SF women in translation or historical fiction by women in translation or poetry by women in translation or plays by women in translation. On the contrary, you're all wonderful. It's just that I once again look back on a WITMonth that - despite being the most active and successful month by far of the past three years! - remained generally cloistered within a certain community.

Like I've said before and will say again - the women in translation project is meant to be as broad as possible. That means it's meant to cover as many possible languages and as many possible genres and as many possible readers as possible. I love the progress we've made on the first front... what about the next?

I don't for a moment want to take away from those readers who have spent the past month championing SF women in translation or historical fiction by women in translation or poetry by women in translation or plays by women in translation. On the contrary, you're all wonderful. It's just that I once again look back on a WITMonth that - despite being the most active and successful month by far of the past three years! - remained generally cloistered within a certain community.

Like I've said before and will say again - the women in translation project is meant to be as broad as possible. That means it's meant to cover as many possible languages and as many possible genres and as many possible readers as possible. I love the progress we've made on the first front... what about the next?

Sunday, August 28, 2016

WITMonth Day 28 | Subtly Worded - Teffi | Review

Short story collections are always a bit problematic. There's a huge difference between collections written as single entities, collections curated from an author's body of work, or collections compiled from different authors (particularly when not written with a specific theme in mind).

Any collection that isn't written ahead of time as a single book often stumbles a bit in my opinion. I have a hard time sticking with the stories, since it often feels like there isn't much of a motivation to read through the collection at once. That was only half true of Teffi's Subtly Worded. On the one hand, Teffi's style is clean and consistent, calmly guiding the reader from one story to another. On the other hand, the stories span so many years that it's a little difficult to read them as one cohesive unit. (I also wasn't entirely clear on how much the translator impacted matters, since while the collection is mostly translated by Anne Marie Jackson and Robert Chandler [from what I could gather...], there were many translators credited and a few stories that felt a bit out of place did in fact turn out to be translated by other translators.)

I'd seen so many positive reviews of Subtly Worded that I came in slightly skeptical as to whether the book would actually be as charming as presented. I'm not sure how I came away. I really enjoyed Teffi's quietly humorous style in some of the stories, and found that the shorter pieces worked really well. But many of the longer stories lost me (particularly the Rasputin story, which was clearly supposed to be a standout sort of tale and most readers seemed to love yet thoroughly bored me).

The collection is sweet in parts, entertaining in others, funny at times and sadly melancholic in others. And it generally flows well. This isn't the sort of collection you start and stop every other story. It's also the sort of collection that makes me confident in Teffi as a writer, and intrigued enough to continue seeking out her works. I'm not sure I loved this collection as much as others, but it was pleasant enough (I really only skipped a few stories) and some of the stories were downright excellent. A pretty good balance for a short story collection, I'd say.

Any collection that isn't written ahead of time as a single book often stumbles a bit in my opinion. I have a hard time sticking with the stories, since it often feels like there isn't much of a motivation to read through the collection at once. That was only half true of Teffi's Subtly Worded. On the one hand, Teffi's style is clean and consistent, calmly guiding the reader from one story to another. On the other hand, the stories span so many years that it's a little difficult to read them as one cohesive unit. (I also wasn't entirely clear on how much the translator impacted matters, since while the collection is mostly translated by Anne Marie Jackson and Robert Chandler [from what I could gather...], there were many translators credited and a few stories that felt a bit out of place did in fact turn out to be translated by other translators.)

I'd seen so many positive reviews of Subtly Worded that I came in slightly skeptical as to whether the book would actually be as charming as presented. I'm not sure how I came away. I really enjoyed Teffi's quietly humorous style in some of the stories, and found that the shorter pieces worked really well. But many of the longer stories lost me (particularly the Rasputin story, which was clearly supposed to be a standout sort of tale and most readers seemed to love yet thoroughly bored me).

The collection is sweet in parts, entertaining in others, funny at times and sadly melancholic in others. And it generally flows well. This isn't the sort of collection you start and stop every other story. It's also the sort of collection that makes me confident in Teffi as a writer, and intrigued enough to continue seeking out her works. I'm not sure I loved this collection as much as others, but it was pleasant enough (I really only skipped a few stories) and some of the stories were downright excellent. A pretty good balance for a short story collection, I'd say.

Saturday, August 27, 2016

WITMonth Day 27 | The Man Who Snapped His Fingers - Fariba Hachtroudi | Review

Let me just start by saying that you should read The Man Who Snapped His Fingers. It's a good book. It's an interesting book. It has flashes of depth that it doesn't always explore fully, but there's enough to contemplate here and to learn from.

The Man Who Snapped His Fingers translated by the excellent Alison Anderson is the sort of novel that catches you just a bit off guard. The flap - once again - does the book a slight disservice, almost trivializing the novel to that of a relationship that isn't exactly as described. So I came into the novel expecting a flatter sort of story, and was instantly hooked by a completely different sort of narrative.

And when I say hooked, I mean hooked.

The story is almost hypnotic in how it pulses, tugs and draws the reader along. The writing is mostly conversational, often direct in its pleas and presentations. There is an urgency in the way the Colonel relates his story, his anxiety, his unhappiness, his love. Compare this with the equally tense but far less dramatic narration from Vima, whose struggles seem all too close. This is the sort of writing that doesn't release you until you're done, and luckily the book isn't too long so as to inconvenience. (I would even go so far as to say that the book felt like it was at exactly the right length, with excellent pacing.)

The alternating narration bothered me less than I expected, because the shift is relatively gradual. First we have the somewhat incoherent ramblings of the Colonel, as he describes his life as a not-yet-refugee (and all the issues it entails...) and the unclear pieces of his past life. The book does not progress chronologically at any point, with narratives refreshed at different points in the novel from different perspectives. It makes The Man Who Snapped His Fingers perhaps a little less straight-forward than it could have been (and perhaps a bit too "loopy"), but the effect is one of a much longer novel, and one with a lasting impact.

All this without having addressed the politics. And The Man Who Snapped His Fingers is full of politics - the politics of love, the politics of refugees, the politics of oppressive regimes, the politics of gender, the politics of propaganda, the politics of manipulation - without ever feeling like it's especially overwhelming. These issues are at the forefront, but not exhausting. They're intriguing and thought-provoking, without weighing down the emotional core of the novel.

And the emotional core itself is political as well. Is it possible to forgive your torturers? Is it possible to forgive yourself? What does a love story look like from the other angle? What happens at the end of a political love story? The Man Who Snapped His Fingers is not exactly a love story, yet it thrums like one and spoke to me on an emotional level not unlike a very different sort of story.

I liked The Man Who Snapped His Fingers a lot. It was a hypnotic read, entrancing and engaging. I found myself thinking about it a lot in the days after reading it. This is definitely one of those WITMonth books I'm glad to have read, and can comfortably recommend onward.

The Man Who Snapped His Fingers translated by the excellent Alison Anderson is the sort of novel that catches you just a bit off guard. The flap - once again - does the book a slight disservice, almost trivializing the novel to that of a relationship that isn't exactly as described. So I came into the novel expecting a flatter sort of story, and was instantly hooked by a completely different sort of narrative.

And when I say hooked, I mean hooked.

The story is almost hypnotic in how it pulses, tugs and draws the reader along. The writing is mostly conversational, often direct in its pleas and presentations. There is an urgency in the way the Colonel relates his story, his anxiety, his unhappiness, his love. Compare this with the equally tense but far less dramatic narration from Vima, whose struggles seem all too close. This is the sort of writing that doesn't release you until you're done, and luckily the book isn't too long so as to inconvenience. (I would even go so far as to say that the book felt like it was at exactly the right length, with excellent pacing.)

The alternating narration bothered me less than I expected, because the shift is relatively gradual. First we have the somewhat incoherent ramblings of the Colonel, as he describes his life as a not-yet-refugee (and all the issues it entails...) and the unclear pieces of his past life. The book does not progress chronologically at any point, with narratives refreshed at different points in the novel from different perspectives. It makes The Man Who Snapped His Fingers perhaps a little less straight-forward than it could have been (and perhaps a bit too "loopy"), but the effect is one of a much longer novel, and one with a lasting impact.

All this without having addressed the politics. And The Man Who Snapped His Fingers is full of politics - the politics of love, the politics of refugees, the politics of oppressive regimes, the politics of gender, the politics of propaganda, the politics of manipulation - without ever feeling like it's especially overwhelming. These issues are at the forefront, but not exhausting. They're intriguing and thought-provoking, without weighing down the emotional core of the novel.

And the emotional core itself is political as well. Is it possible to forgive your torturers? Is it possible to forgive yourself? What does a love story look like from the other angle? What happens at the end of a political love story? The Man Who Snapped His Fingers is not exactly a love story, yet it thrums like one and spoke to me on an emotional level not unlike a very different sort of story.

I liked The Man Who Snapped His Fingers a lot. It was a hypnotic read, entrancing and engaging. I found myself thinking about it a lot in the days after reading it. This is definitely one of those WITMonth books I'm glad to have read, and can comfortably recommend onward.

Friday, August 26, 2016

WITMonth Day 26 | Another (less short) interlude

WITMonth is a lot about reading books, but it can also be about reading reviews, stats posts, ideas, and essays! So here are a few more links of cool things I've spotted throughout WITMonth. As always, I'm unable to link to every single wonderful post or blogger or outlet. But that doesn't make your content any less amazing!

Some cool things to check out, read and explore:

Some cool things to check out, read and explore:

- #WITMonth on Instagram! Lots of cool pics and displays, definitely giving me more ideas for next time...

- BookRiot has had not one, but four posts covering WITMonth! Some great recommendations looking ahead, plus a wonderful post by M. Lynx Qualey about how we can advance the cause from here.

- PEN America continued their series on the women in translation project, most recently posting about winners of the PEN Translation Prize which were translated by women.

- Men in translation recommended women in translation.

- Many wonderful bloggers continued contributing excellent reviews and WITMonth content, including (but not limited to!): Word by Word, Tony's Reading List, The Writes of Woman, JacquiWine's Journal, 1streading, Messengers Booker, HerStory Novels, way more bloggers I'm missing (sorry sorry sorry!), and of course the whole Twitter tag which is basically just a trick to convince you to read loads more amazing books! Many readers compiled lists throughout the month which are definitely worth checking out too.

- Granta Magazine published a story by Silvina Ocampo for WITMonth!

- Estandarte published a general piece on WITMonth (in Spanish), encouraging the project to be expanded into other languages as well (I am in full agreement).

- The New York Public Library posted a great list of Yiddish women writers in translation.

- Words Without Borders published an extensive list of 31 books by women writers in translation worth checking out.

- TANK Magazine spotlighted works by women in translation.

- The Women in Translation Tumblr continues to be an excellent resource in every way, shape and form.

As always, I know I'm forgetting so much excellent WITMonth content... but here's just a taste. There were also lots of great giveaways, photos, tweets, recommendations and lists floating around! It is well worth going through the #WITMonth tag on Twitter, in my opinion, and scouting around for excellent books. Your TBR will come away far richer for it.

We still have a few more days of WITMonth, but that doesn't mean our work is done! More to come...

Thursday, August 25, 2016

WITMonth Day 25 | Plans for future reading

Anyone who's followed this blog for a couple years will likely know one important fact about me: I cannot stick to a reading plan.

So yeah. I didn't read most of the books I thought I'd be reading during WITMonth. I read other books and will read others still, with even moe books prepped for the future. Will I read these books in the next hear? Who knows? But here are some books I've been recommended or randomly found of am just excited about:

So yeah. I didn't read most of the books I thought I'd be reading during WITMonth. I read other books and will read others still, with even moe books prepped for the future. Will I read these books in the next hear? Who knows? But here are some books I've been recommended or randomly found of am just excited about:

- Butterflies in November by Auður Ava Ólafsdótti (translated by Brian FitzGibbon). This was recommended to me by a friend last year, actually, and I picked it up at a bargain the other day!

- History by Elsa Morante (translated by William Weaver). This is one of those classics that's been on my radar for too long, and I finally just decided: I'm buying it, I'm reading it, good day.

- The First Wife by Paulina Chiziane (translated by David Brookshaw). This is one of those books that's cropped up a lot in WITMonth lists this year. I saw it at the bookstore and it just felt right, so... Really looking forward to it!

- In Other Words by Jhumpa Lahiri (translated by Ann Goldstein). This feels like an important one to explore.

- The Queue by Basma Abdel Aziz (translated by Elisabeth Jaquette). The hype has convinced me, and I'm excited.

- Ladivine by Marie NDiaye (translated by Jordan Stump). I mean, this one was always going to be on the list. I haven't loved everything I've read by NDiaye, but her writing is always so interesting.

- Fish in a Dwindling Lake by Ambai (translated by Lakshmi Holmström). I'm still trying to expand my horizons more when it comes to Southeast Asia and India in particular, and this was one of the few titles I was able to track down via my digital library! Looking forward to finding as many more as possible.

- Human Acts by Han Kang (translated by Deborah Smith). This is on my list. Quite obviously. I don't even need to explain this.

...and there are so many other books that look amazing from people's wonderful reviews. From wonderful write-ups. From wonderful lists. Or photos or references or just random ideas tossed around. It's been amazing to watch, but I can hear my already-overflowing bookshelves sobbing before I present them with all these new and diverse books I can't wait to read.

Wednesday, August 24, 2016

WITMonth Day 24 | Christine de Pizan | Thoughts

One of my personal victories from WTMonth is discovering Christine de Pizan. You might argue that it's more a sign of my earlier flaws as a reader (that I didn't know of her existence until two years ago...), but I choose to view it more positively. Here was a woman writing of feminist ideas before feminism even existed, exploring gender dynamics and topics of utmost importance to women (even today!) in 1405! And I found her!

I began with The Book of the City of Ladies, which was, in fact, better than I had expected. I came prepared to be somewhat bored, to find the text exhausting in its casual sexism and racism, reductionist and absurd all at once, while intriguing in its concept. Yet while it's obviously an old text and the cultural context is very different from our current one, Christine's writing felt shockingly modern. In fact, parts felt like they could have just as easily been written by a modern feminist blogger today.

The Treasure of the City of Ladies continued along a similar vein. The two books are very different in their message (and thus their morality...), but both had this undercurrent vibe of: You're raising the exact same issues modern feminists raise today, but you're reaching completely different conclusions. Christine's morality is inherently tied to Christianity (and a very specific type of Christianity at that), further influenced by general cultural norms of the time. That means it's lacking much of the inclusive warmth modern feminism has rightly adopted (and intersectionality as a notion is pretty much limited to Christine pointing out that women of lower social classes are not meaningless, though she spends little time arguing the point...), and there is a rigid expectation of conduct that makes little sense in today's world.

This can make for uncomfortable reading in parts, though I found it fascinating. Take, for instance, Christine's advice on how women ought to treat their husbands. On the one hand, she advocates for wives to be docile and adhere to their husbands rule (even when those husbands may be cruel or abusive). But beneath that seemingly anti-feminist message lurks another odd little piece of advice: Wives, be wise enough in the workings of your estate and your husband's work to be able to advise him. While clearly sticking to the existing tradition by which wives must serve their husbands (and suffer in silence), Christine also pointedly fights for women to have basic (and not so basic) education. Don't be passive, she argues. Don't be ignorant. Don't...

Don't let men take advantage of you when you're widowed. Because that's what it appears happened to Christine upon her husband's death. In her memoirs, she writes almost dispassionately about the various men who saw an opportunity to swindle a young widow and about the legal woes she was forced into as a result. It makes you wonder, though, how much of the advice Christine gives in The Treasure is borne of bitterness. She so often dwells on how a wife must be kind and accommodating to her husband's friends, but what happened to her? Was she taken advantage of by friends, or rather did those kinder men help her? Is the advice ironic, through clenched teeth, or is Christine again recognizing a world which would hurt women in every possible way and one tiny way which might help them?

It was the moments of pure feminism, though, that fascinated me most. Imagine the audacity of a 15th century woman writing pointedly that no woman has ever encouraged rape or sought it out. Or discussing - flatly, furiously, ferociously - that women are not inherently less intelligent than men, nor less virtuous, nor more frivilous, nor incapable of learning, nor lesser beings. The Book of the City of Ladies is a treasure-trove of passionate arguments against claims that are still depressingly prevalent, with immediate retorts to things like "women's vanity" (Christine coolly points to the prevalence of deeply vain men in the French court), rape (she was asking for it has apparently been the argument for hundreds of years, but feminists weren't having it then and they won't have it now), women's intelligence (including Christine smugly referencing her own intelligence, in a rather gratifying bit of self-glorification) or education (for which Christine strongly advocates). These are the sorts of topics I still find fascinating today.

And I also loved the way things weren't the same. I loved seeing the differences between Christine's demands for basic rights as compared to modern feminist theory. I loved seeing the way Christine almost predicts the sorts of questions women will be asking 600 years later, or the problems they might face (even if her suggestions seem hilariously outdated). I loved having to put on my 15th-century glasses in order to try to rebuild Christine's truest meaning. I loved her observations, her sharpness, her breadth, her passion and her insistence. Here was a woman who recognized the important role she played. Yes, that is radical.

I've now read 2.5 books of Christine de Pizan's writing (multiple translators and editions); I hope to read everything of hers that has been translated into English. While representing only one perspective (I would love, for instance, to read contemporary texts from other parts of the world!), Christine is a sharp, witty, intelligent writer with a lot to say and her works are well worth reading. Not just her pre-feminist texts either, but also her poetry, her stories, her criticism...

Then I wonder... Why isn't Christine de Pizan on the list of the greats? Why is she not more frequently discussed as a pre-feminist, an important stepping stone to equal rights long before the feminist movement even existed? Or is she actually that prevalent... and only I was unaware...?

*** I also find myself wondering why the academic consensus seems to be to refer to her as "Christine" (and nothing further); if it's just an overly-familiar sexist thing or for some other reason...?

I began with The Book of the City of Ladies, which was, in fact, better than I had expected. I came prepared to be somewhat bored, to find the text exhausting in its casual sexism and racism, reductionist and absurd all at once, while intriguing in its concept. Yet while it's obviously an old text and the cultural context is very different from our current one, Christine's writing felt shockingly modern. In fact, parts felt like they could have just as easily been written by a modern feminist blogger today.

The Treasure of the City of Ladies continued along a similar vein. The two books are very different in their message (and thus their morality...), but both had this undercurrent vibe of: You're raising the exact same issues modern feminists raise today, but you're reaching completely different conclusions. Christine's morality is inherently tied to Christianity (and a very specific type of Christianity at that), further influenced by general cultural norms of the time. That means it's lacking much of the inclusive warmth modern feminism has rightly adopted (and intersectionality as a notion is pretty much limited to Christine pointing out that women of lower social classes are not meaningless, though she spends little time arguing the point...), and there is a rigid expectation of conduct that makes little sense in today's world.

This can make for uncomfortable reading in parts, though I found it fascinating. Take, for instance, Christine's advice on how women ought to treat their husbands. On the one hand, she advocates for wives to be docile and adhere to their husbands rule (even when those husbands may be cruel or abusive). But beneath that seemingly anti-feminist message lurks another odd little piece of advice: Wives, be wise enough in the workings of your estate and your husband's work to be able to advise him. While clearly sticking to the existing tradition by which wives must serve their husbands (and suffer in silence), Christine also pointedly fights for women to have basic (and not so basic) education. Don't be passive, she argues. Don't be ignorant. Don't...

Don't let men take advantage of you when you're widowed. Because that's what it appears happened to Christine upon her husband's death. In her memoirs, she writes almost dispassionately about the various men who saw an opportunity to swindle a young widow and about the legal woes she was forced into as a result. It makes you wonder, though, how much of the advice Christine gives in The Treasure is borne of bitterness. She so often dwells on how a wife must be kind and accommodating to her husband's friends, but what happened to her? Was she taken advantage of by friends, or rather did those kinder men help her? Is the advice ironic, through clenched teeth, or is Christine again recognizing a world which would hurt women in every possible way and one tiny way which might help them?

It was the moments of pure feminism, though, that fascinated me most. Imagine the audacity of a 15th century woman writing pointedly that no woman has ever encouraged rape or sought it out. Or discussing - flatly, furiously, ferociously - that women are not inherently less intelligent than men, nor less virtuous, nor more frivilous, nor incapable of learning, nor lesser beings. The Book of the City of Ladies is a treasure-trove of passionate arguments against claims that are still depressingly prevalent, with immediate retorts to things like "women's vanity" (Christine coolly points to the prevalence of deeply vain men in the French court), rape (she was asking for it has apparently been the argument for hundreds of years, but feminists weren't having it then and they won't have it now), women's intelligence (including Christine smugly referencing her own intelligence, in a rather gratifying bit of self-glorification) or education (for which Christine strongly advocates). These are the sorts of topics I still find fascinating today.

And I also loved the way things weren't the same. I loved seeing the differences between Christine's demands for basic rights as compared to modern feminist theory. I loved seeing the way Christine almost predicts the sorts of questions women will be asking 600 years later, or the problems they might face (even if her suggestions seem hilariously outdated). I loved having to put on my 15th-century glasses in order to try to rebuild Christine's truest meaning. I loved her observations, her sharpness, her breadth, her passion and her insistence. Here was a woman who recognized the important role she played. Yes, that is radical.

I've now read 2.5 books of Christine de Pizan's writing (multiple translators and editions); I hope to read everything of hers that has been translated into English. While representing only one perspective (I would love, for instance, to read contemporary texts from other parts of the world!), Christine is a sharp, witty, intelligent writer with a lot to say and her works are well worth reading. Not just her pre-feminist texts either, but also her poetry, her stories, her criticism...

Then I wonder... Why isn't Christine de Pizan on the list of the greats? Why is she not more frequently discussed as a pre-feminist, an important stepping stone to equal rights long before the feminist movement even existed? Or is she actually that prevalent... and only I was unaware...?

*** I also find myself wondering why the academic consensus seems to be to refer to her as "Christine" (and nothing further); if it's just an overly-familiar sexist thing or for some other reason...?

Tuesday, August 23, 2016

WITMonth Day 23 | WIT in every language | Thoughts

I've been challenged on this point a few times in recent months, so let's talk about it: The women in translation project need not be limited to translations into English. Moreover, it should not be limited to translations into English.

I don't have stats for what publishing looks like in most other languages, nor do I have much of a quantitative clue as to what translations into those other languages look like. I do know - from my own observations - that translations from English make up a huge proportion of translations into Hebrew, German and French. I also know that while many English-language women writers get translated, women writing in non-English "foreign" languages also seem missing from the shelves in non-English languages.

The women in translation project applies to everyone, everywhere.

As I've said many times, the point of this project is to broaden our horizons as much as possible. This isn't always practical - in Hebrew, for example, it's fairly unlikely to find a translator who can work directly from a Korean or Bengali text. This makes it pretty difficult to gain access to these books (though in very rare cases, books like these will simply undergo double translation via the English - I'll get back to this in a moment) and expecting the same sort of availability as in other, more global languages (like... English) is pretty ridiculous. This is a real complication.

But that doesn't completely absolve us. Languages like Hebrew or Icelandic or any other language may have relatively few speakers/readers (or just few potential translators!), but the need for diversity in translation isn't erased simply because it's harder to get those books. Sure, the ratios might look different (and they should!), but the infrastructure for translations - and thus for the women in translation project - needs to be there. It's as important as in English.

Let's get back to English for a moment. I've had people criticize the women in translation project for being inherently Anglo-centric, what with the fact that I am referring almost exclusively to works translated into English. The argument is not entirely wrong, and indeed there is a bias in how I generally conduct my research. That said, I cannot help but note the reality in which the English-language literary market influences the rest of the world far more than any other market influences back. Translations into Hebrew, for example, are overwhelmingly from English. Translations from other languages often come only after the translation into English has succeeded/gained prominence. And again the matter of double-translations arise, in which many languages simply have no overlap and need a convenient language bridge (though this is not always English, of course...).

The women in translation project looks different in other languages, yes. Sometimes it might focus on the native language stats and gender breakdown. Sometimes it might focus on all translations into that language (including English-language). Sometimes it might mean looking for books from languages that fairly inaccessible. Sometimes it might just be the English-language WIT project question: Why aren't our existing women writers being translated into English (or other languages)?

I don't ask these questions as often, true, and I haven't ever devoted much time to them on the blog (mostly because I've never fully quantified my observations and ideas; laziness and lack of resources). But they're questions we should be open to asking. They're questions we should be encouraging. They're questions we - at least those of us who can - should be exploring the answers to. What does the women in translation project look like in other languages? I would love to know.

I don't have stats for what publishing looks like in most other languages, nor do I have much of a quantitative clue as to what translations into those other languages look like. I do know - from my own observations - that translations from English make up a huge proportion of translations into Hebrew, German and French. I also know that while many English-language women writers get translated, women writing in non-English "foreign" languages also seem missing from the shelves in non-English languages.

The women in translation project applies to everyone, everywhere.

As I've said many times, the point of this project is to broaden our horizons as much as possible. This isn't always practical - in Hebrew, for example, it's fairly unlikely to find a translator who can work directly from a Korean or Bengali text. This makes it pretty difficult to gain access to these books (though in very rare cases, books like these will simply undergo double translation via the English - I'll get back to this in a moment) and expecting the same sort of availability as in other, more global languages (like... English) is pretty ridiculous. This is a real complication.

But that doesn't completely absolve us. Languages like Hebrew or Icelandic or any other language may have relatively few speakers/readers (or just few potential translators!), but the need for diversity in translation isn't erased simply because it's harder to get those books. Sure, the ratios might look different (and they should!), but the infrastructure for translations - and thus for the women in translation project - needs to be there. It's as important as in English.

Let's get back to English for a moment. I've had people criticize the women in translation project for being inherently Anglo-centric, what with the fact that I am referring almost exclusively to works translated into English. The argument is not entirely wrong, and indeed there is a bias in how I generally conduct my research. That said, I cannot help but note the reality in which the English-language literary market influences the rest of the world far more than any other market influences back. Translations into Hebrew, for example, are overwhelmingly from English. Translations from other languages often come only after the translation into English has succeeded/gained prominence. And again the matter of double-translations arise, in which many languages simply have no overlap and need a convenient language bridge (though this is not always English, of course...).

The women in translation project looks different in other languages, yes. Sometimes it might focus on the native language stats and gender breakdown. Sometimes it might focus on all translations into that language (including English-language). Sometimes it might mean looking for books from languages that fairly inaccessible. Sometimes it might just be the English-language WIT project question: Why aren't our existing women writers being translated into English (or other languages)?

I don't ask these questions as often, true, and I haven't ever devoted much time to them on the blog (mostly because I've never fully quantified my observations and ideas; laziness and lack of resources). But they're questions we should be open to asking. They're questions we should be encouraging. They're questions we - at least those of us who can - should be exploring the answers to. What does the women in translation project look like in other languages? I would love to know.

Monday, August 22, 2016

WITMonth Day 22 | The pipeline | Thoughts

We're losing women writers in translation.

We're losing women writers in translation at every stage: in biases back home in native languages, in reviews, in the pamphlets sent out to foreign-language publishers, in the books the publishers sample, in the books they ultimately translate, in the books they then promote, in the books then reviewed by foreign/English-language papers, in the books made comfortably available to average readers in libraries and bookstores, and then straight back to the books that even seem plausible for acquisition and marketing (based on sales).

It's a frustrating realization because it almost feels as though it's out of my hands. I've talked about what roles we all play in terms of actively supporting the women in translation project, and how I believe the problem is too complex to reduce to a single responsible party. Yet seeing how many stages exist before a book can even get to readers makes me wonder at the structural changes that would need to occur.

Should we maybe talk about quotas for awards or review pages? Is it time to discuss those publishers that maintain abysmal rates of translating women writers and ask ourselves what leads to such imbalances? Should we ask ourselves who are the people in charge of review pages or award panels that manage to ignore women writers in translation so thoroughly, and what might be the reason? Are there further institutional biases at play that we need to be considering? Is there something we can be doing differently?

I have often presented the facts and huge disparities between men and women writers. Every post - about awards, publishing, reviews, etc. - feels like I'm uncovering another leak in a pipeline from which women writers are far more likely to spill. Sometimes it feels like we're doing a great job of bringing in new water containers (book recommendations! WITMonth! an award for women in translation!), but the pipes keep leaking because we haven't actually gotten to them yet. Much as I'm grateful for all the new water (and I am)... wouldn't it be great if we could just fix the pipeline itself?

We're losing women writers in translation at every stage: in biases back home in native languages, in reviews, in the pamphlets sent out to foreign-language publishers, in the books the publishers sample, in the books they ultimately translate, in the books they then promote, in the books then reviewed by foreign/English-language papers, in the books made comfortably available to average readers in libraries and bookstores, and then straight back to the books that even seem plausible for acquisition and marketing (based on sales).

It's a frustrating realization because it almost feels as though it's out of my hands. I've talked about what roles we all play in terms of actively supporting the women in translation project, and how I believe the problem is too complex to reduce to a single responsible party. Yet seeing how many stages exist before a book can even get to readers makes me wonder at the structural changes that would need to occur.

Should we maybe talk about quotas for awards or review pages? Is it time to discuss those publishers that maintain abysmal rates of translating women writers and ask ourselves what leads to such imbalances? Should we ask ourselves who are the people in charge of review pages or award panels that manage to ignore women writers in translation so thoroughly, and what might be the reason? Are there further institutional biases at play that we need to be considering? Is there something we can be doing differently?

I have often presented the facts and huge disparities between men and women writers. Every post - about awards, publishing, reviews, etc. - feels like I'm uncovering another leak in a pipeline from which women writers are far more likely to spill. Sometimes it feels like we're doing a great job of bringing in new water containers (book recommendations! WITMonth! an award for women in translation!), but the pipes keep leaking because we haven't actually gotten to them yet. Much as I'm grateful for all the new water (and I am)... wouldn't it be great if we could just fix the pipeline itself?

Sunday, August 21, 2016

WITMonth Day 21 | The Happiness of Kati by Jane Vejjajiva | Review

Jane Vejjajiva's The Happiness of Kati (translated by Prudence Borthwick) is a strange sort of children's book. The simplicity of the storytelling reminded me of several similar books I'd read around middle school (aged 11-12 or so), where heavy topics are handled in an almost deliberately simplified manner alongside surprisingly complex prose. These sorts of in-between books (not quite kid-lit, not yet YA) can often feel like with just a bit of editing they'd work better in either direction: simpler language and vocabulary to serve as pure children's books, or slightly more nuanced storytelling to serve as a YA/adult-friendly novel.

The language in The Happiness of Kati felt a bit overblown at times, with fancy vocab words and elegant sentences. I didn't always feel like it sat so well with the simplicity of the sentence-structures, and the very straightforward way protagonist Kati tells her story.

The plot too is very simplified. This isn't exactly the story of a child dealing with a missing parent, or a disabled parent, or adjusting to a new normal. There's no blatant beginning-to-end narrative that is usually found in children's books. Nor is the book simply a series of Kati's observations. Kati's story remains fixated around her - whatever she's going through, so goes the story. It's a bit messy from a storytelling perspective, but it also makes the ending more thought-provoking. It also means that if you find yourself drawn to Kati - which I did - you'll be able to appreciate anything the book throws your way, because you appreciate Kati and her thought process.

There are a lot of ways in which The Happiness of Kati might challenge a young reader's thinking. First and foremost, the book is not written to explain Thai culture in any explicit manner. Instead, readers can learn that different cultures are the natural order of things without any of the exoticism that many adult-geared novels employ in order to bridge the culture gap. The book is also interesting in its rather bleak focus on ALS. Kati's introduction to ALS (and serious illness in general) may serve the young reader as well, with its frank examination of disability and death. It's not the most sensitive way to talk about such big issues and would likely require further critical examination outside of the narrative itself, but it can serve as a reasonable base for some readers.

Kati's simple approach to life (and happiness) is warmly appealing, and even alongside some of the structural flaws, The Happiness of Kati is a pleasant and thought-provoking little book. Though I think it might be an awkward fit for some children (in terms of advanced language not always meshing with the simple storytelling style), I enjoyed it reasonably enough and imagine I would have found it very interesting as a child.

The language in The Happiness of Kati felt a bit overblown at times, with fancy vocab words and elegant sentences. I didn't always feel like it sat so well with the simplicity of the sentence-structures, and the very straightforward way protagonist Kati tells her story.

The plot too is very simplified. This isn't exactly the story of a child dealing with a missing parent, or a disabled parent, or adjusting to a new normal. There's no blatant beginning-to-end narrative that is usually found in children's books. Nor is the book simply a series of Kati's observations. Kati's story remains fixated around her - whatever she's going through, so goes the story. It's a bit messy from a storytelling perspective, but it also makes the ending more thought-provoking. It also means that if you find yourself drawn to Kati - which I did - you'll be able to appreciate anything the book throws your way, because you appreciate Kati and her thought process.

There are a lot of ways in which The Happiness of Kati might challenge a young reader's thinking. First and foremost, the book is not written to explain Thai culture in any explicit manner. Instead, readers can learn that different cultures are the natural order of things without any of the exoticism that many adult-geared novels employ in order to bridge the culture gap. The book is also interesting in its rather bleak focus on ALS. Kati's introduction to ALS (and serious illness in general) may serve the young reader as well, with its frank examination of disability and death. It's not the most sensitive way to talk about such big issues and would likely require further critical examination outside of the narrative itself, but it can serve as a reasonable base for some readers.

Kati's simple approach to life (and happiness) is warmly appealing, and even alongside some of the structural flaws, The Happiness of Kati is a pleasant and thought-provoking little book. Though I think it might be an awkward fit for some children (in terms of advanced language not always meshing with the simple storytelling style), I enjoyed it reasonably enough and imagine I would have found it very interesting as a child.

Saturday, August 20, 2016

WITMonth Day 20 | Home by Leila S. Chudori | Review

Home by Leila S. Chudori (translated by John H. McGlynn) is exactly the sort of book that I had hoped the women in translation project would lead me to. Not only am I basically illiterate when it comes to Indonesian literature, I know very little about Indonesian history or culture. Home - written in large part from an expat perspective and examining the culture of leaving - naturally delves into many of the introductory topics an uneducated reader like myself would benefit from.

The book centers on an Indonesian political exile Dimas Suryo, occasionally shifting perspective but focused in its first half on his new life in Paris (with brief flashbacks to his youth in Indonesia). In the second half, the focus shifts to his half-French daughter Lintang, who is effectively forced to confront her muddled background by her university advisor. Though the change felt abrupt when it occurred, Lintang soon overtook her father in terms of being an engaging and interesting narrator. Her story unfolds more traditionally and echoed in my mind for weeks after I finished the book.

There were moments in the first half of Home that felt simply like history lessons, recited for the sake of memorializing still ignored atrocities. Other moments felt like Cultural Lessons, though some of them oddly enough went largely forgiven by the narrative (for example: the scene in which Lintang's professor condescendingly advises her to talk about her Indonesian heritage for her thesis, as though this is all she is allowed to be - exotic).

Still, it was hard to ignore the power of the story. Dimas' anxiety over having left his homeland behind is a familiar story for those who have read enough immigrant fiction (or... those who have lived it), similarly it's hard not to feel strongly for him when he thinks about the torture and suffering left behind. The book also doesn't shy about the political ramifications even in exile, where the restaurant Dimas and his friends found is viewed as "subversive" for Indonesian nationals, and even the next generation (like Lintang) as suspect.

Home shifts gears in Lintang's section, becoming a very different sort of novel. If the first part is a classic exile/expat novel, the second is a classic return-from-diaspora story. Lintang reluctantly acknowledges her need/desire to visit the "homeland", and once there is drawn into the intricacies of daily life. She meets the children of her fathers' friends, she meets her cousins, she discovers the stain her father's name still carries (and its real-world implications on her family), and she falls into a comfortable sort of pattern. Plotwise, this part of the story was a bit too predictable in my mind, but it worked well enough and didn't drag down the narrative.

It's in this final section that Chudori also introduces Segra Alam, the son of Dimas' former lover and friend. Alam is a familiar sort of man, with a common enough sort of subversiveness and rebellion (in a subversive and rebellious group of friends). His narration usually simply complements Lintang's, but he also serves as a mouthpiece for the more liberal and frustrated youth: "[H]istory is owned not just by the power holders but also by the materialistic middle class who cuddle up to them." There's a bitterness to his narration which contrasts Lintang's more expansive view, and though I didn't necessarily love his sections, I appreciated the way they fit together with the larger story.

The book centers on an Indonesian political exile Dimas Suryo, occasionally shifting perspective but focused in its first half on his new life in Paris (with brief flashbacks to his youth in Indonesia). In the second half, the focus shifts to his half-French daughter Lintang, who is effectively forced to confront her muddled background by her university advisor. Though the change felt abrupt when it occurred, Lintang soon overtook her father in terms of being an engaging and interesting narrator. Her story unfolds more traditionally and echoed in my mind for weeks after I finished the book.

There were moments in the first half of Home that felt simply like history lessons, recited for the sake of memorializing still ignored atrocities. Other moments felt like Cultural Lessons, though some of them oddly enough went largely forgiven by the narrative (for example: the scene in which Lintang's professor condescendingly advises her to talk about her Indonesian heritage for her thesis, as though this is all she is allowed to be - exotic).

Still, it was hard to ignore the power of the story. Dimas' anxiety over having left his homeland behind is a familiar story for those who have read enough immigrant fiction (or... those who have lived it), similarly it's hard not to feel strongly for him when he thinks about the torture and suffering left behind. The book also doesn't shy about the political ramifications even in exile, where the restaurant Dimas and his friends found is viewed as "subversive" for Indonesian nationals, and even the next generation (like Lintang) as suspect.

Home shifts gears in Lintang's section, becoming a very different sort of novel. If the first part is a classic exile/expat novel, the second is a classic return-from-diaspora story. Lintang reluctantly acknowledges her need/desire to visit the "homeland", and once there is drawn into the intricacies of daily life. She meets the children of her fathers' friends, she meets her cousins, she discovers the stain her father's name still carries (and its real-world implications on her family), and she falls into a comfortable sort of pattern. Plotwise, this part of the story was a bit too predictable in my mind, but it worked well enough and didn't drag down the narrative.

It's in this final section that Chudori also introduces Segra Alam, the son of Dimas' former lover and friend. Alam is a familiar sort of man, with a common enough sort of subversiveness and rebellion (in a subversive and rebellious group of friends). His narration usually simply complements Lintang's, but he also serves as a mouthpiece for the more liberal and frustrated youth: "[H]istory is owned not just by the power holders but also by the materialistic middle class who cuddle up to them." There's a bitterness to his narration which contrasts Lintang's more expansive view, and though I didn't necessarily love his sections, I appreciated the way they fit together with the larger story.

Ultimately, Home is an interesting and powerful novel, one worth reading and thinking over. It's a book that lingers in your consciousness, not to mention the way the characters seem unwilling to leave your mind even weeks after reading. I truly felt as though Lintang and I were close friends, and for several days after finishing Home I could hear her voice ringing in my head. The writing is clear and straight-forward, without much overemphasis or exoticism. Even as there were plot points I felt were lacking or characters that weren't developed enough (particularly near the end), I found that I liked the flow of the novel. I also liked the somewhat open-ended way the novel closed, though I recognize that many readers might walk away somewhat disappointed.

The one great flaw, however, is the edition, which is riddled with copy errors. Every few pages I felt myself thrown out of the story by a missing quotation mark or comma or period. At first I thought, "okay, it's just a few..." but then it kept repeating itself. However much I liked the content, I can't pretend that my reading experience wasn't somewhat tainted by this. One or two mistakes are to be expected. Dozens? Not so much.

Even so, I can comfortably recommend Home. This is a well-written and interesting account not only of Indonesian history, but of the exile and diaspora experiences as a whole. Well-written (if poorly edited) with intensely drawn characters, Home is a strong novel well worth your time.

The one great flaw, however, is the edition, which is riddled with copy errors. Every few pages I felt myself thrown out of the story by a missing quotation mark or comma or period. At first I thought, "okay, it's just a few..." but then it kept repeating itself. However much I liked the content, I can't pretend that my reading experience wasn't somewhat tainted by this. One or two mistakes are to be expected. Dozens? Not so much.

Even so, I can comfortably recommend Home. This is a well-written and interesting account not only of Indonesian history, but of the exile and diaspora experiences as a whole. Well-written (if poorly edited) with intensely drawn characters, Home is a strong novel well worth your time.

Friday, August 19, 2016

WITMonth Day 19 | An interlude | #7favWITreads

Feel free to tweet your own!

#7favWITreads

DISCLAIMER: These are not all of my favorites. That's impossible, of course... These are just some, with a few recent reads that are still lurching around my brain.

Enjoy!

#7favWITreads

DISCLAIMER: These are not all of my favorites. That's impossible, of course... These are just some, with a few recent reads that are still lurching around my brain.

Enjoy!

- Kalpa Imperial by Angélica Gorodischer (translated by Ursula K. Le Guin)

- The Bridge of Beyond by Simone Schawz-Bart (translated by Barbara Bray)

- The Story of a New Name by Elena Ferrante (translated by Ann Goldstein)

- The Book of the City of Ladies by Christine de Pizan (translated by Rosalind Brown-Grant)

- The End of Days by Jenny Erpenbeck (translated by Susan Bernofsky)

- Home by Leila Chudori (translated by John H. McGlynn)

- The Vegetarian by Han Kang (translated by Deborah Smith)

Thanks to Jacqui of JacquiWine's Journal for suggesting this great idea!

Thursday, August 18, 2016

WITMonth Day 18 | Reviews of women in translation | Stats

After several years of anecdotal references, hand-waving and uncertainty, it's about time we figure out what's happening on the end of review outlets when it comes to women writers in translation. Let's dive in, shall we?

Methodology

I looked at only a very small sample of review outlets, attempting more to gauge an impression of the existing situation than the sort of truly representative work that outlets like VIDA do. The four journals I focused on were Three Percent Review, The Guardian (features and reviews separately), Asymptote, and Words Without Borders. These four were chosen based on my familiarity with them more than anything and may as a result have led to somewhat biased results. All data collected is from August 2015 through August 2016 (WITMonth to WITMonth, basically).

The three possible outcomes

There are three scenarios in terms of review rates:

The Guardian - Reviews and Features

I began by looking at The Guardian's "Literature in Translation" section first, largely because of their literary prominence and visibility in the literary world. I decided to distinguish between specifically defined reviews and features/news articles fairly early in collecting my data. This came about when I noticed that Elena Ferrante's name seemed to crop up a disproportionate amount. Indeed, I soon realized that the Guardian's results skewed heavily if each feature on Elena Ferrante was counted as a separate piece focusing on women writers: Ferrante featured in no less than seven pieces, whether discussing her popularity or her actual origins (is she a man?! no?!) or the books themselves (less common). Two other authors also featured double (superstar Haruki Murakami and Chen Xue whose work appeared twice in Asymptote's Translation Tuesday series).

Thus looking only at authors featured, we see a fairly predictable distribution: 30% women writers, 70% men writers. I soon realized, however, that Asymptote's not-quite weekly feature seemed to have more women writers than average. Indeed, the Translation Tuesday series had a 41% publication rate for women. Adjusting for this "tilt", I checked the features again without this one series: the ratio plummets to 21%.

The situation did not improve much in reviews. Out of 41 reviews of literature in translation, only 22% were of books written by women writers. Here there was no need to skew or adjust, quite simply: The Guardian reviews fewer women writers in translation than men. Beyond the industry bias, The Guardian employs further hurdles for women writers in translation, leading to reduced visibility and awareness. (This despite the fact that they have featured two articles specifically on the matter of women writers in translation, non-author-specific articles which were included in the features count.)

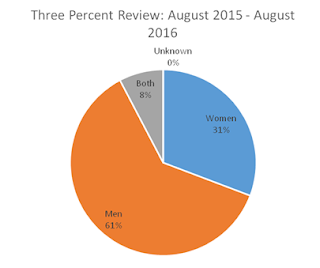

Three Percent Review

While Three Percent Review does not have the same visibility or popularity of The Guardian, Three Percent is highly regarded in the world of literature in translation. Furthermore, the site has discussed the imbalance in publishing women writers in translation themselves. It seemed only fitting to see how they did. It turns out that the Three Percent Review follows the industry standard almost perfectly, even including the 8% of titles by various authors. Three Percent Review is the epitome of option number one as described above: They display a perfect random sampling of the existing bias. No more, no less.

Asymptote Journal

After noting Asymptote's high translation rate of short stories and excerpts in The Guardian, I decided to check their actual reviews page. Here, it turned out, they do a significantly poorer job, clocking in at a low 22%. This result surprised me after the pleasantly corrective Translation Tuesday rates at the Guardian. Different editors, perhaps?

Words Without Borders

Finally, I checked one of the most central websites for literature in translation: Words Without Borders. WWB is the site that many consider to have launched the discussion about women writers in translation (with Alison Anderson's original piece in 2013), and they recently posted their own WITMonth reading list. The rate here is a bit dull: 35% is slightly better than the industry average, but it doesn't quite wash away the bad taste of a huge imbalance. While I didn't look at their features and every article in every issue (I encourage any intrepid readers to map that out!), my impression is again of a site that takes what is offered. Despite honest attempts to find women writers from around the world (and WWB do seek to include women writers even when looking at more "difficult" regions of the world), they're just not able to break through that ratio.

What these results mean

Once again, I should note that it's difficult to claim these results as representative when I sampled only four review outlets. Unfortunately, I do not have the resources at hand that an organization like VIDA utilizes, nor the time to fully analyze the results to the levels that I would like.

But as always, a pattern emerges that does not bode well for the women in translation movement. The fact that review outlets are not attempting at the very least to even the playing field in terms of publicity is disappointing, though it may not be their fault. We ask ourselves: what books are publishers promoting or sending for review? Furthermore, the sloppy way in which some outlets review their women writers is even more depressing. In one Guardian review, the reviewer noted with subtle sexism: "There is something about the way Hochet presents us with the mental processes of a rootless 45-year-old womaniser that suggests a writer of unusual ability. These days, authors seem to stick to speaking for their own gender more than they used to."

It's disappointing to see this imbalance, but it represents another area in which we simply need to try a bit harder. For literature in translation reviews inherently pick from a smaller pool of books than those that are written in English. We know that the good books by women are out there (and indeed I noticed that many fan-favorites among WITMonth book bloggers did not make the "official" review cut in these outlets) and we know that it's possible to reach 20 excellent books by women writers alongside 20 excellent books by men writers. Parity - at this stage, at least - is entirely possible.

Methodology

I looked at only a very small sample of review outlets, attempting more to gauge an impression of the existing situation than the sort of truly representative work that outlets like VIDA do. The four journals I focused on were Three Percent Review, The Guardian (features and reviews separately), Asymptote, and Words Without Borders. These four were chosen based on my familiarity with them more than anything and may as a result have led to somewhat biased results. All data collected is from August 2015 through August 2016 (WITMonth to WITMonth, basically).

The three possible outcomes

There are three scenarios in terms of review rates:

- The standard 30%/70% publishing ratio. While a typically low rate, this would indicate that the outlet effectively "samples at random". There is neither an attempt at corrective discrimination, nor any additional bias being taken into account.

- Women in translation at a higher rate than the publishing average of 30%. This would probably indicate awareness on the side of the review outlet and an attempt to "correct" the problematic rates, seeking at the very least media parity.

- Women in translation at a lower rate than the publishing average of 30%. This indicates an outlet that includes a further level of bias against women writers, beyond a random sampling. This could be as the result of biased perceptions when it comes to "quality literature", similar to the overall review bias found by VIDA.

The Guardian - Reviews and Features

I began by looking at The Guardian's "Literature in Translation" section first, largely because of their literary prominence and visibility in the literary world. I decided to distinguish between specifically defined reviews and features/news articles fairly early in collecting my data. This came about when I noticed that Elena Ferrante's name seemed to crop up a disproportionate amount. Indeed, I soon realized that the Guardian's results skewed heavily if each feature on Elena Ferrante was counted as a separate piece focusing on women writers: Ferrante featured in no less than seven pieces, whether discussing her popularity or her actual origins (is she a man?! no?!) or the books themselves (less common). Two other authors also featured double (superstar Haruki Murakami and Chen Xue whose work appeared twice in Asymptote's Translation Tuesday series).

Thus looking only at authors featured, we see a fairly predictable distribution: 30% women writers, 70% men writers. I soon realized, however, that Asymptote's not-quite weekly feature seemed to have more women writers than average. Indeed, the Translation Tuesday series had a 41% publication rate for women. Adjusting for this "tilt", I checked the features again without this one series: the ratio plummets to 21%.

Three Percent Review

While Three Percent Review does not have the same visibility or popularity of The Guardian, Three Percent is highly regarded in the world of literature in translation. Furthermore, the site has discussed the imbalance in publishing women writers in translation themselves. It seemed only fitting to see how they did. It turns out that the Three Percent Review follows the industry standard almost perfectly, even including the 8% of titles by various authors. Three Percent Review is the epitome of option number one as described above: They display a perfect random sampling of the existing bias. No more, no less.

Asymptote Journal

After noting Asymptote's high translation rate of short stories and excerpts in The Guardian, I decided to check their actual reviews page. Here, it turned out, they do a significantly poorer job, clocking in at a low 22%. This result surprised me after the pleasantly corrective Translation Tuesday rates at the Guardian. Different editors, perhaps?

Words Without Borders

Finally, I checked one of the most central websites for literature in translation: Words Without Borders. WWB is the site that many consider to have launched the discussion about women writers in translation (with Alison Anderson's original piece in 2013), and they recently posted their own WITMonth reading list. The rate here is a bit dull: 35% is slightly better than the industry average, but it doesn't quite wash away the bad taste of a huge imbalance. While I didn't look at their features and every article in every issue (I encourage any intrepid readers to map that out!), my impression is again of a site that takes what is offered. Despite honest attempts to find women writers from around the world (and WWB do seek to include women writers even when looking at more "difficult" regions of the world), they're just not able to break through that ratio.

What these results mean

Once again, I should note that it's difficult to claim these results as representative when I sampled only four review outlets. Unfortunately, I do not have the resources at hand that an organization like VIDA utilizes, nor the time to fully analyze the results to the levels that I would like.

But as always, a pattern emerges that does not bode well for the women in translation movement. The fact that review outlets are not attempting at the very least to even the playing field in terms of publicity is disappointing, though it may not be their fault. We ask ourselves: what books are publishers promoting or sending for review? Furthermore, the sloppy way in which some outlets review their women writers is even more depressing. In one Guardian review, the reviewer noted with subtle sexism: "There is something about the way Hochet presents us with the mental processes of a rootless 45-year-old womaniser that suggests a writer of unusual ability. These days, authors seem to stick to speaking for their own gender more than they used to."

It's disappointing to see this imbalance, but it represents another area in which we simply need to try a bit harder. For literature in translation reviews inherently pick from a smaller pool of books than those that are written in English. We know that the good books by women are out there (and indeed I noticed that many fan-favorites among WITMonth book bloggers did not make the "official" review cut in these outlets) and we know that it's possible to reach 20 excellent books by women writers alongside 20 excellent books by men writers. Parity - at this stage, at least - is entirely possible.

Wednesday, August 17, 2016

WITMonth Day 17 | The Lake by Banana Yoshimoto | Review

The Lake by Banana Yoshimoto (translated by Michael Emmerich) joins the too-long list of books with woefully inaccurate book jacket descriptions. The blurb on the inside flap makes The Lake sound like a book full of distant, unloving characters and a pervasive mystery. It's makes it sound like a dark thriller lurking behind a facade of a "quirky" love story.

It's not. And it is much better for it.

The Lake is actually a genuinely sweet story, framed by the "mystery" and oddness Nakajima, its male lead. Told from the perspective of the somewhat lonely - but otherwise kindhearted - Chihiro, the book tracks the two's slow and somewhat tentative love story. I use the word tentative to contrast "hesitant" (as used in the book jacket description) in large part because it's not that there are any indicators that either Nakajima or Chihiro are actually hesitant about entering a relationship, rather that their relationship progresses somewhat awkwardly and non-traditionally.

As a love story, there's something oddly endearing about it. Chihiro is constantly asking herself when exactly she fell in love (whether she fell in love), but her actions and behavior display how strongly she feels even when she can't quite figure it out herself. It's harder to understand Nakajima, and not just because he isn't the narrator. Nakajima is, as Chihiro notes, odd. He doesn't share everything and Chihiro knows that there are parts of him he's hiding.

But I loved the moments in which both are just normal young adults fumbling in love. The discussion the two have about their careers (Chihiro is a painter, Nakajima a biology/medical student) was almost laugh-out-loud refreshing for me, in how naturally the conversation flowed (and felt eerily familiar; the question of whether people are capable of understanding what scientists do is a conversation I've had many times...). The book also carefully examines Chihiro's relationship with her parents, a piece of her history that is complicated and difficult at times, but doesn't weigh down her story.

There were other little things that I liked a lot, too. Unlike The Briefcase, where I felt that the characters were all so cold and distant, Chihiro and Nakajima both felt living and breathing. More than that, I loved the small characterization of Chihiro as someone who cares for children. While it may seem like a minor detail, it was the sort of tiny character piece that made her seem more human and... warm. I was able to care about her. And even though Nakajima is a distant character by definition, I found that I cared about him as well, from the small moments where he reveals insecurities (despite how difficult it is for him), to more simple scenes like when he and Chihiro discuss food.

The book flows pretty well, though the writing at first felt a bit jerky and out of place. On the one hand, the bulk of the story can be condensed into a pretty short piece, but parts of it felt like long, quiet meditations. The book overall is quite short and quite a quick read, balancing these two effects out for the most part. Though I felt that the beginning and the focus on Chihiro's family didn't always fit in with the later pieces (and that the ending came on just a bit abruptly and info-dump-y), the writing is clear and simple and never quite stops. It feels like the book could have gone on for another hundred pages (or another thousand) just as easily. And though I would have wanted about five more pages of denouement and a slower final reveal, it feels like the story ultimately ended at pretty much the right place. The right feel.

The Lake isn't a loud book. It doesn't try to shout any message, and it sometimes fumbles its own plot just a little bit. It's not the most lyrical writing you'll find and it's not the most staccato storytelling and it isn't filled with the most sharply "quirky" or unique characters you'll ever meet. But I liked it. I liked it a lot. It's sweet and warm in just the right way, emotionally engaging without being overwhelming. This might not be the book for everyone, but if you're looking for a fairly quiet love story with questions of self and the nature of love itself, The Lake is a pretty good choice.

It's not. And it is much better for it.

The Lake is actually a genuinely sweet story, framed by the "mystery" and oddness Nakajima, its male lead. Told from the perspective of the somewhat lonely - but otherwise kindhearted - Chihiro, the book tracks the two's slow and somewhat tentative love story. I use the word tentative to contrast "hesitant" (as used in the book jacket description) in large part because it's not that there are any indicators that either Nakajima or Chihiro are actually hesitant about entering a relationship, rather that their relationship progresses somewhat awkwardly and non-traditionally.

As a love story, there's something oddly endearing about it. Chihiro is constantly asking herself when exactly she fell in love (whether she fell in love), but her actions and behavior display how strongly she feels even when she can't quite figure it out herself. It's harder to understand Nakajima, and not just because he isn't the narrator. Nakajima is, as Chihiro notes, odd. He doesn't share everything and Chihiro knows that there are parts of him he's hiding.

But I loved the moments in which both are just normal young adults fumbling in love. The discussion the two have about their careers (Chihiro is a painter, Nakajima a biology/medical student) was almost laugh-out-loud refreshing for me, in how naturally the conversation flowed (and felt eerily familiar; the question of whether people are capable of understanding what scientists do is a conversation I've had many times...). The book also carefully examines Chihiro's relationship with her parents, a piece of her history that is complicated and difficult at times, but doesn't weigh down her story.

There were other little things that I liked a lot, too. Unlike The Briefcase, where I felt that the characters were all so cold and distant, Chihiro and Nakajima both felt living and breathing. More than that, I loved the small characterization of Chihiro as someone who cares for children. While it may seem like a minor detail, it was the sort of tiny character piece that made her seem more human and... warm. I was able to care about her. And even though Nakajima is a distant character by definition, I found that I cared about him as well, from the small moments where he reveals insecurities (despite how difficult it is for him), to more simple scenes like when he and Chihiro discuss food.