After several years of anecdotal references, hand-waving and uncertainty, it's about time we figure out what's happening on the end of review outlets when it comes to women writers in translation. Let's dive in, shall we?

Methodology

I looked at only a very small sample of review outlets, attempting more to gauge an impression of the existing situation than the sort of truly representative

work that outlets like VIDA do. The four journals I focused on were

Three Percent Review,

The Guardian (features and reviews separately),

Asymptote, and

Words Without Borders. These four were chosen based on my familiarity with them more than anything and may as a result have led to somewhat biased results. All data collected is from August 2015 through August 2016 (WITMonth to WITMonth, basically).

The three possible outcomes

There are three scenarios in terms of review rates:

- The standard 30%/70% publishing ratio. While a typically low rate, this would indicate that the outlet effectively "samples at random". There is neither an attempt at corrective discrimination, nor any additional bias being taken into account.

- Women in translation at a higher rate than the publishing average of 30%. This would probably indicate awareness on the side of the review outlet and an attempt to "correct" the problematic rates, seeking at the very least media parity.

- Women in translation at a lower rate than the publishing average of 30%. This indicates an outlet that includes a further level of bias against women writers, beyond a random sampling. This could be as the result of biased perceptions when it comes to "quality literature", similar to the overall review bias found by VIDA.

The Guardian - Reviews and Features

I began by looking at The Guardian's "Literature in Translation" section first, largely because of their literary prominence and visibility in the literary world. I decided to distinguish between specifically defined reviews and features/news articles fairly early in collecting my data. This came about when I noticed that Elena Ferrante's name seemed to crop up a disproportionate amount. Indeed, I soon realized that the Guardian's results skewed heavily if each feature on Elena Ferrante was counted as a separate piece focusing on women writers: Ferrante featured in no less than

seven pieces, whether discussing her popularity or her actual origins (

is she a man?!

no?!) or the books themselves (less common). Two other authors also featured double (superstar Haruki Murakami and Chen Xue whose work appeared twice in Asymptote's Translation Tuesday series).

Thus looking only at

authors featured, we see a fairly predictable distribution: 30% women writers, 70% men writers. I soon realized, however, that Asymptote's not-quite weekly feature seemed to have more women writers than average. Indeed, the Translation Tuesday series had a 41% publication rate for women. Adjusting for this "tilt", I checked the features again

without this one series: the ratio plummets to 21%.

The situation did not improve much in reviews. Out of 41 reviews of literature in translation, only 22% were of books written by women writers. Here there was no need to skew or adjust, quite simply: The Guardian reviews fewer women writers in translation than men. Beyond the industry bias, The Guardian employs further hurdles for women writers in translation, leading to reduced visibility and awareness. (This despite the fact that they have featured two articles specifically on the matter of women writers in translation, non-author-specific articles which

were included in the features count.)

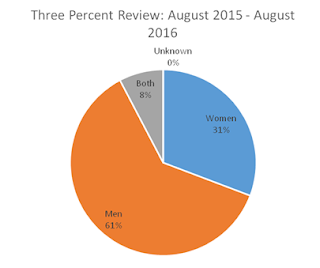

Three Percent Review

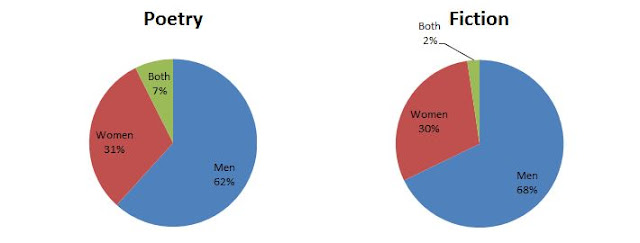

While Three Percent Review does not have the same visibility or popularity of The Guardian, Three Percent is highly regarded in the world of literature in translation. Furthermore, the site has discussed the imbalance in publishing women writers in translation themselves. It seemed only fitting to see how they did. It turns out that the Three Percent Review follows the industry standard almost perfectly, even including the 8% of titles by various authors. Three Percent Review is the epitome of option number one as described above: They display a perfect random sampling of the existing bias. No more, no less.

Asymptote Journal

After noting Asymptote's high translation rate of short stories and excerpts in The Guardian, I decided to check their actual reviews page. Here, it turned out, they do a significantly poorer job, clocking in at a low 22%. This result surprised me after the pleasantly corrective Translation Tuesday rates at the Guardian. Different editors, perhaps?

Words Without Borders

Finally, I checked one of the most central websites for literature in translation: Words Without Borders. WWB is the site that many consider to have launched the discussion about women writers in translation (with Alison Anderson's original piece in 2013), and they recently posted their own WITMonth reading list. The rate here is a bit dull: 35%

is slightly better than the industry average, but it doesn't quite wash away the bad taste of a huge imbalance. While I didn't look at their features and every article in every issue (I encourage any intrepid readers to map that out!), my impression is again of a site that takes what is offered. Despite honest attempts to find women writers from around the world (and WWB

do seek to include women writers even when looking at more "difficult" regions of the world), they're just not able to break through that ratio.

What these results mean

Once again, I should note that it's difficult to claim these results as representative when I sampled only four review outlets. Unfortunately, I do not have the resources at hand that an organization like VIDA utilizes, nor the time to fully analyze the results to the levels that I would like.

But as always, a pattern emerges that does not bode well for the women in translation movement. The fact that review outlets are not attempting at the very least to even the playing field in terms of publicity is disappointing, though it may not be their fault. We ask ourselves: what books are publishers promoting or sending for review? Furthermore, the sloppy way in which some outlets

review their women writers is even more depressing. In one Guardian review, the reviewer

noted with subtle sexism: "

There is something about the way Hochet presents us with the mental processes of a rootless 45-year-old womaniser that suggests a writer of unusual ability. These days, authors seem to stick to speaking for their own gender more than they used to."

It's disappointing to see this imbalance, but it represents another area in which we simply need to try a bit harder. For literature in translation reviews inherently pick from a smaller pool of books than those that are written in English. We

know that the good books by women are out there (and indeed I noticed that many fan-favorites among WITMonth book bloggers did not make the "official" review cut in these outlets) and we

know that it's possible to reach 20

excellent books by women writers alongside 20

excellent books by men writers. Parity - at this stage, at least - is entirely possible.